Wendy Bohon: From Actor to Earthquake Expert

13 September 2021

Wendy Bohon majored in theatre in college and moved out to LA to become an actor after graduation. So how did she end up becoming an earthquake geologist and the Senior Science Communication Specialist for the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology?

We talked to Wendy about her unconventional career path on our latest Sci & Tell episode. She told us about how the Hector Mine earthquake changed her entire career path, overcoming imposter syndrome (hint: it involves a therapy folder), and she even dispels some misconceptions people have about earthquakes. Oh, there’s also a statue of her- and she didn’t even have to die for it.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and Nisha Mital, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: Hey Sci & Tell listeners, Shane here. I’m going to start this episode a little differently. Usually I have a personal story that somehow relates to what we talked about with our interviewee, and honestly, the best one I have is about experiencing an earthquake and having no idea what it was. If you’re interested I suggest you go back and listen to our interview with volcanologist Melissa Scruggs. But for this one I just wanted to thank our interviewee, Wendy Bohon, up front. Full disclosure, we’re friends, but that’s not why we chatted with her today. Since I’ve known Wendy I’ve asked her help out with numerous projects across multiple organizations that I work for. And no matter how busy she is or what’s on her plate, she always says yes. Words can’t describe how appreciative I am of that so I’m very excited to give her a platform to share all sorts of wonderful experiences and advice for future generations (and, I’ll add, I learned a little bit about Wendy myself)!

Shane M Hanlon: Everyone has a story, even, or maybe especially, scientists. Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it. From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: Alright, let’s get into it. I’m gonna bring in Nisha introduce Wendy and this episode.

Nisha Mital: Hey! For this episode we talked to Wendy Bohon, who’s an earthquake geologist and the Senior Science Communication Specialist at IRIS. If you’ve ever wondered how to become a scientist with a degree in theater, then this is definitely the episode for you.

Shane M Hanlon: It’s pretty wild. When folks ask me how to become a science communicator, I tell them that there’s no set path. Wendy is a great example of that and I’m excited for this interview. Our interviewer for this one was Paul Molin.

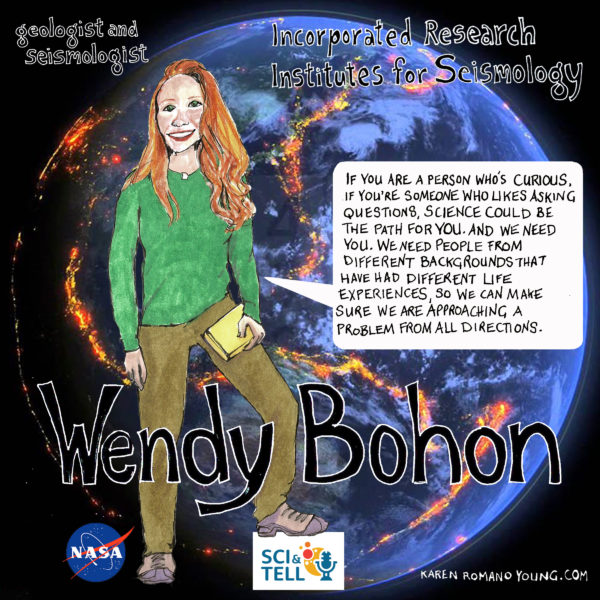

Dr. Wendy Bohon: I am Dr. Wendy Bohon. I'm an earthquake geologist and the Senior Science Communication Specialist for the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology, IRIS, for short, not the IRS. Don't call us about any checks, IRIS. And my job, one of the cool things about it is that it is different every day. So I do meetings and emails, just like everybody with every single job, but I also handle all of the outward facing stuff for my organization. So I do science writing, I handle content for the webpage. I do social [00:00:30] media and I do a lot of talks. So whenever there's a big earthquake I talk to different kinds of media about what that meant.

And I put out the products that my organization provides, which is mainly related to seismic data from around the world. And I talk to teachers, I talk to students and then I also teach scientists how to talk to different audiences like the public, because scientists, aren't trained to talk to people they're trained to talk to other scientists. So if we really want our science to get used, we have [00:01:00] to teach the scientist how to communicate it to the people that can use it.

Paul Molin: So you wear a lot of hats?

Dr. Wendy Bohon: I wear a lot of hats, but they're fun hats.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: So this is a funny story. Actually I never saw myself as a scientist. In high school and even before that, I was very much an artist. So I went to school for theater, particularly Shakespearian stage acting. So my undergraduate degree is a BA in Theater. While I was there, I did take some geology classes and ended up picking geology up as a second major but then I wasn't focused on that, it just a cool thing. [00:03:00] I went to school in the mountains in Virginia and was interested in the world around me and my dad is a naturalist so I was exposed to science, but I was an artist. So I ended up moving to LA to be an actor. And while I was there, I felt the Hector Mine earthquake, which was a magnitude 7.1 out in the desert, but it was strongly felt all over Southern California and it was amazing.

It was terrifying, but it was just amazing. So the next day I went to the USGS in Pasadena, the United States Geological [00:03:30] Survey, they handle things like earthquakes and floods and geology, minerals, those sorts of things for the US and asked to volunteer. And they said, "No." Don't go to the USGS the day after a large earthquake has been felt in an urban area. They're a little bit busy-

Paul Molin: Good for you.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: ... but I persisted. I went back and I was taken on as a volunteer, worked with a woman named Lisa Wald. And eventually they were like, "Wow, you're actually really good at this. Do you want to come here and work?" And I was like, "Yeah." [00:04:00] So I started working for the USGS and a few years later, I became the Education and Outreach Specialist for the USGS Earthquake Hazards program for Southern California. And I loved it because it was a great integration of the geology and my theater skills, talking to people, creating materials for the public and lawmakers and different stakeholders. And I really felt like I was making an impact in people's lives, helping them to understand something that could be dangerous, that they were scared of. [00:04:30] And I thought, "This is what I want to do." So then I went back to grad school and got a master's degree and a PhD in Earthquake Geology. So the path was non linear.

Paul Molin: Wow, I mean it was a very 180 moment for you.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: It was, and I've come back around of course, because now I'm back to doing more of the outreach and communication side, but alongside the science. And so I [00:05:00] talk to people a lot about failure and how failure is just a stepping stone to success, right? So I felt like a failure because I left acting and I felt like I hadn't succeeded at that. When in reality, I was just chasing something else I wanted to do, which is totally fine to do, but nobody says, "Oh, it's okay to change careers. It's okay to totally change what you're doing." And then when you go to grad school, the idea is that if you don't go [00:05:30] on to become a research scientist, then you're not a real scientist.

And that is just crazy talk because there's lots of different ways to use a scientific background in service to society that's not just research. And so by choosing to go into science communication, as opposed to going into getting a research position or being a professor that felt like a failure, but that was other people telling me that that choice was a failure, right? For me, it was a success because this is what I [00:06:00] really love to do. So it's just part of it is recognizing what's best for you.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: The biggest hurdle, I think that I've had to get over, there have been a lot. The biggest one is myself. We all know the things that we think we're good at and not good at. And I felt for a long time like I didn't belong in science at all. And particularly in geology, which is a very male dominated field. I had [00:08:30] seen myself as an artist for so long that I had a really hard time seeing myself as a scientist. And so I had a really hard time believing that anyone else would see me that way. And so there was a lot of kind of imposter syndrome. And then you couple that with the fact that there's not a lot of other women that are doing that in those spaces and it can be really, really hard to get out of my own head about things.

And so it took a long time for me to recognize, "Wow, I actually am really good at this and I really [00:09:00] do belong here." And so I want to make sure that I make space for other people that may want to do that and have a lot to contribute, but don't feel like they're welcome or don't see themselves in that light.

Paul Molin: How do you get there? How do you make that turn? Is it just experience and time? How do you gain that confidence to realize, "I do belong here?"

Dr. Wendy Bohon: Experience, and time is important. And also your crew, the people that are around [00:09:30] you, that lift you up that support you and that reflect a different version of you back to yourself. So I have really great friends and colleagues and coworkers that helped me to see beyond what I see in myself, right? Because we all know the mistakes that we make, we all know our own shortcomings really well, but that's not necessarily how the world perceives us. And so you kind of need yourself reflected back from someone else's perspective to say, "Wow, okay."

And so I posted [00:10:00] something on Twitter the other day. I have a folder in my email that's, "Nice things people say about me." And I put emails in there where people have sent compliments or thanked me for different things so that I can go back and see kind of the impact that I've made. And those moments where I'm having a lot of struggle or having a lot of self doubt I go back and I'm like, "Wow, but this person I really respect thinks this about me," or "I really helped this student in this way. So my career and the things I'm doing are actually making an impact, [00:10:30] even if I can't get out of my own head in this moment."

Paul Molin: You have your own little therapy folder.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: I do.

Paul Molin: So pre pandemic, what would you have noted as your greatest personal achievement or work achievement?

Dr. Wendy Bohon: Well, so I'm a AAAS If/Then Ambassador, science ambassador. So it's my responsibility in that role to be a high profile [00:12:30] role model for young women in science, or that are interested in STEM careers. The idea being that if you can see it, then you can be it. If you don't see people in these spaces are doing these jobs, you don't think that it's something maybe that is meant for you, maybe something you haven't even considered. And so there's 100 of us around the country in all different kinds of fields. We're in museums and we're on TV, and we do all of these different things. And, does this sound cool? There [00:13:00] is a statue of each one of us, a full-size statue of all of us in Dallas. And it has a QR code and you can read about what we do and our accomplishments and see pictures of us doing our work. And that is the coolest thing. I have a statue and I didn't even have to die first.

Paul Molin: That or donate a lot of money.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: Right. People don't go into science to make a lot of money, so that's a good thing because it didn't have any money to donate.

Paul Molin: That's awesome.

Dr. Wendy Bohon: That's pretty cool. Something I never expected for sure.

Paul Molin: [00:16:00] A lot of people react to earthquakes differently than you did, right? They don't run and try and figure out how to help her learn more. What do you think the biggest misconception about earthquakes is?

Dr. Wendy Bohon: Oh man, there's so many. People are afraid that the ground is going to swallow them up during earthquakes because you sometimes see pictures of these cracks in the ground. And that's actually not what happens. The fault [00:16:30] is sliding and if you don't have the fault touching, it's not going to actually create any energy waves, kind of like snapping your fingers. If you don't push your fingers together, they don't create energy waves when they move. And when you see cracks like that, that's a secondary effect of the shaking. So that's usually a landslide or some other kind of unstable ground that moved during the earthquake shaking. So the ground is not like the movies where it opens and swallows up cars or cities or anything like that. Other misconceptions, [00:17:00] there's an old thing that people were told to do to stand in a doorway when you feel earthquake shaking, that's not advisable now in today's modern construction.

Buildings are generally pretty safe here in the United States. And so what you want to do when you feel shaking from an earthquake is drop down to the ground, take cover underneath the sturdy object, and then hold onto that object because the force of the shaking can actually exceed the force of gravity and so the table, or whatever you're underneath can actually [00:17:30] kind of bounce or ricochet away from you. So you want to hold on because the biggest danger now comes from things falling on you. So you want to protect yourself from bookcases or dishes, anything that could fall and hurt you.

Paul Molin: And how do you fight the misconceptions or get the information out to... I went to elementary school in California. So I remember earthquake drills and lining the hallways, our hands behind her necks and things like that. [00:18:00] But I feel like it's harder when people are adults and they still have misconceptions or they learn the wrong way. I hadn't heard not to do a doorway. I mean, I remember hearing that growing up. How do you get that information out to people?

Dr. Wendy Bohon: It's tough. You have to number one, meet people where they are, right? You have to understand why they believe the things that they believe in order to explain how things have changed since they learned what they learned. And it's important [00:18:30] to do that in lots of different ways, because some people only read newspapers. Some people are only on the internet. Other people only listen to the radio so you have to make sure you're covering all of those types of bases. And then you have to make sure that you're speaking to people in ways that are meeting their needs. You don't want to scare people into inaction, but you also have to impress upon them the severity and the seriousness of what you're talking about, which is a delicate line to walk. Also, you have to make sure that you're talking to people [00:19:00] from lots of different backgrounds, right?

So that requires that there's lots of different languages, making sure that we are also speaking to people that may have disabilities, then aren't able to do the things that we recommend in the ways that we recommend them. So we have to make sure we have all of this different messaging lined up. So we're meeting the needs of the at-risk population for whatever the hazard may be. So it's complicated and the messenger matters, right? Because trust is critical. If [00:19:30] you want people to change their behavior, they have to trust you and believe you.

And it's not just based on your expertise. It's also, do they feel like you're being compassionate and empathetic towards them? Do you actually care about them and their lives and the choices that they're making? So there's a whole lot of different things that go into communicating about something like earthquakes, because as a scientist, we're excited by them. It's a new opportunity to learn things. And of course our [00:20:00] goal is always to apply that knowledge, to keep people safe and to keep organizations and communities and cities safer, but it can come across as callous when we're like, "Whoa, that was amazing, that earthquake was so cool," because it affects real people. It affects real people's lives and businesses. It causes serious anxiety. People just want to keep themselves and their family safe. And we have to keep that at the forefront of our mind and at the forefront of our communication.

Paul Molin: What advice do you give to young people who are considering a work life in the sciences, whether it's [00:39:30] geology or any other field?

Dr. Wendy Bohon: I would say science is one of many paths that you can take to make an impact and make a difference in the world. If you are a person that's curious, if you're someone that likes asking questions, science could be the path for you. Science, technology, engineering, math, any of the STEM fields could be a good path for you. And we need you. We need people from different backgrounds [00:40:00] that have had different life experiences so that we can make sure that we are approaching a problem from all directions. Because if you have just one sort of person thinking about a particular problem, they're coming at it usually from just one angle and that may not be the best approach.

So if we really want to solve, today's very important global problems, we need to have the full cohort of people on board thinking about those things. And the [00:40:30] best and brightest minds come in all different kinds of bodies from all different kinds of places. So we are working hard. There are a lot of us that are working hard to make the culture of science better, to make it safer, to make it more welcoming. So we are working hard to make sure that when you come to science or technology engineering, that you have a good place where you can thrive, not just sort of survive the culture or whatever. So hopefully young folks by the time you get here, [00:41:00] it'll be a really nice place to work where you can focus on problems and find really good solutions.

Paul Molin: When you talk to those groups of women and those little girls, what is your message to them?

Dr. Wendy Bohon: You do belong. As women, we're told in a lot of different ways that we're not [00:41:30] welcome in certain spaces, that we are less than, and that starts early, that starts in elementary school that boys are better at math and girls are better at English. And even I, in my career have now started looking back and been like, "Wow, some of my imposter syndrome wasn't actually imposter syndrome. It was gaslighting. It was people telling me in ways, large and small that I as a woman didn't belong, I was too weak to do field work. I wasn't strong enough to carry the equipment." All of which is not true. So that wasn't [00:42:00] me. That was messaging from outside of me that I was internalizing.

And so I would tell girls that you are every bit as smart as the boys, you are every bit as good at math. You are every bit as capable and competent as other people. And that kind of is across the board. Just because we have this conception of who can be a scientist, what a scientist looks like, that is wrong. And I reject that completely. So [00:42:30] that's what I want to tell them is that I am giving you an invitation. You are welcome and needed in science.

Nisha Mital: It can be really hard to persevere as a girl who’s interested in STEM. I was a math nerd in middle school, and my primary form of enjoyment was attending math competitions. But I still remember how discouraged I felt in high school when the environment became so much more intense for girls- I went to a STEM focused high school, and there were more girls than boys enrolled, but even so it got to the point where all the girls quit the math team. I ended up becoming an English major in college, but I am so inspired by my friends who are out pursuing Ph.D’s and M.D’s in different STEM fields, and who are bringing their unique interests and backgrounds to their studies to improve their fields. Wendy’s right- girls are welcome and needed in science, and your experiences and backgrounds are essential.

Shane M Hanlon: Well said and thanks to Wendy to sitting down to talk with. Special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible, to Nisha for producing, and to Paul Molin for conducting the interview.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From these scientists in our respective home studios, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.