Prosanta Chakrabarty: Pushing for Global (Fish) Science

26 July 2021

As much as Prosanta Chakrabarty loves his job as an ichthyology professor at LSU, his favorite part of the job is making human connections while doing fieldwork around the world. And whether it’s trying every single cocktail at a bar in Tanzania or trash talking bosses in Bengali to locals in Kuwait, Prosanta has made tons of great connections and memories throughout his career. We talked to Prosanta about knowing he wanted to be a zoologist from a young age, discovering new fish around the world, and partying in the middle of the Amazon River.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and Nisha Mital, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: I’m a herpetologist by training, meaning that I study amphibians and reptiles – frogs, salamanders, turtles, snakes, that kind of stuff. And a lot of my work was out in the field – trudging through swamps and streams, setting up giant cattle tanks to create artificial ponds, and trapping in ponds. On one occasion I was out with a friend setting up turtle traps – they’re big hoop nets that kind of resemble finger traps – the turtle goes in but can’t get back out. I’m literally chest deep in this pond when I hear, “Shane, don’t move, there’s a cottonmouth literally a foot behind you.” That’s a very venomous snake that just happened to be in the water right beside me…just kind of staring at me. I probably stood there for a few minutes until finally it turned and swam away, at which time I beelined it out of there. I’m a herpetologist, yes, but venomous snakes were never really my thing. I’ll stick to frogs and turtles…or maybe I should’ve gotten into fish…

Shane M. Hanlon: Everyone has a story, even, or maybe, especially, scientists. Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it. From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: I’m really excited for today. As an ecologist by training, I don’t get many opportunities to inject my research background into my work at AGU. But today, I do. I wanna bring in my co-producer Nisha to introduce this episode. Hi Nisha.

Nisha Mital: Hi Shane

Shane M Hanlon: OK, can you give us a little preview of our next interview?

Nisha Mital: Sure. For this episode we talked to Prosanta Chakrabarty, an ichthyologist at Louisiana State University. He talked to us about everything from discovering new fish, to partying in the middle of the Amazon River, among other things.

Shane M Hanlon: Our interviewer was Paul Molin.

Prosanta Chakrabarty: I'm Prosanta Chakrabarty. I'm a professor and curator of fishes at Louisiana State University, but this year I'm on sabbatical doing a Fulbright in Ottawa, Canada.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (00:56):

The proposal I wrote was to do instead of deep time evolution stuff that I usually do, to do more what's going on right now in the world, in the world of fishes anyway. And so collecting things in the Ottawa River and elsewhere, just to figure out if building dams and having introduced species come in changes the populations so that we could study them long-term, but more evolution and action stuff, but very much in line with my ichthyology background that I have.

Paul Molin (02:17): When you are back home in Baton Rouge, what are your roles there look like?

Prosanta Chakrabarty (02:25):

Yeah. I do a 50% research, 50% teaching and 50% curation. So that means I teach a one semester a year, usually in the fall. So either teaching ichthyology, the study of fishes or evolution, and sort of alternate between those two, among some smaller classes if I have time and then always doing research, trying to figure out the tree of life and how fishes evolve and what that can tell us about evolutionary history or geological history. And planning trips, we'd like to do two, three international trips a year to collect fishes, to study them abroad, usually in the neotropics or Asia somewhere. So the day to day it's a lot of almost like everybody else sitting in front of the computer, checking email, seeing what the fires I can put out. Day to day is checking that to-do list and see what's up.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (03:38):

I grew up in New York city and there wasn't a lot of wildlife per se to look at. But I loved going to zoos and museums and watching like Marty Stouffer, Wild Kingdom kind of shows. They always, animals always got me interested in the world and I remember distinctly being five or six and looking up at the dinosaurs at the American museum and asking my dad like what is a person who studies animals called? And he said, zoologists. And I'm like, all right, that's what I'm going to be. There wasn't much more to it. And I'm sure like every kid has I want to be a fireman, policeman or whatever, astronaut. And I just picked something I was able to really find a passion for and so for me it was zoology. And I was lucky, I just found the right people to help me along that path.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (07:45):

I remember the big thing was working as a kid at like the Brooklyn aquarium and I was a volunteer and I didn't really meet even then the scientists behind the scenes. And I was like, I don't know what this is. And I just still really liked animals. I was like, I'm going to go to a school that has zoology. And my parents had taken me to Montreal where I was actually born, but didn't live there very long because when I was one, my family moved to New York. And we went to Montreal and we saw this school McGill and it just looked like a castle. I don't think, I remember seeing a university that was sort of separated from the rest of the city, like Queens college in New York or NYU, it's just buildings sort of haphazardly strewn around, but then you have to go through these gates to get to McGill.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (08:43):

And I was like, oh, that'd be cool to come here. I think it was maybe junior high or high school, early high school. And they had a zoology program. And I'd been saying I wanted to be a zoologist without really what it meant. I was like, I should find a school that has it. So I went to McGill, got that zoology degree. A few chance encounters led me to do an undergrad research experience in the summer at the American museum of natural history, which is the, the night at the museum, the famous museum with the dinosaurs plus lots of other stuff. And I worked with a wonderful person named Melanie Stiassny over that summer who taught me all about fishes. And I loved her. She was just like incredibly charming and smart and knowledgeable and described a new species with her and she kind of put me in the club to like know and all the other cool ichthyologists and sent me to a conference.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (09:44):

I, after that, graduating from McGill, I went on to work for a year at the Bronx zoo in the Bronx, ironically. Applied for grad schools, got into the university of Michigan where I did a PhD for five years. And that got me even deeper into the woods of ichthyology. Did a postdoc back at the American museum in New York. So I spent two more years doing that and got my gig at LSU in 2008. I had a pretty straight path, I really knew what I wanted to do early on and sort of stuck with it and had the luck of having the right people sort of hold my hand through the hard parts where I didn't understand. And from then it was all about helping other people get up there too. I had a pretty quick and narrow path, didn't have to do like a master's in something I didn't want to do, or lots of undergrad projects and things not related to what I wanted to do. So I was pretty lucky.

Paul Molin (10:54):

What do you think as you look back on where you are now and the stuff you've done in your career, what are the some of the highlights for you at this point?

Prosanta Chakrabarty (11:05):

For me, I always think about being in the field. So just taking students out in the field, the people I've met in the field, just like funny experiences with students. I remember like my postdoc advisor, John Sparks, who I went to Singapore with, he introduced me on the plane it's like salivating and it's like, oh, we're going to Singapore. We're going to have roti canai, it's the most delicious snack food. How good can it be? He describes, it's like thin flaky bread and you dip it in Curry. I'm like, ah, whatever. And then I have it. It's like, oh my God this is great. And then, when I took my student like 10 years later and I'm like on the plane, oh man, roti canai is so good. Singapore has the best food. I can't wait until you try it. And he's like, oh, what's the big deal. Then it's like a cycle. Things like that, they're great, you go from junior to senior really quick in academia. And for me, just the experiences of giving back to the students, the same way that people gave back to me that's been really rewarding.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (16:11):

In Tanzania, there was this sort of shady bar, but it had an epic drink every day. If it's a place where you think you'd get the local beer baby and hope it's cold, but they always had this really complicated cocktail, the cocktail of the day. And I'd always get that, no matter what it was, always like agave cider with bubble tea something and then like rum, and I was like, I'll have that. And at the end of my trip I took a picture with the bartender who had been making me all these drinks and he was on Facebook. I was like, I'll tag him on Facebook and just sort of like "best bartender in Tanzania." And then underneath all his friends are like, congratulations like as if he had won an award, or got like five stars from Michelin or something. It's things like that. I just love meeting local people.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (17:11):

In the middle east, I was in Kuwait. And I don't know if you know about this, each middle Eastern country, the locals have these kind of like high power jobs. And then the people cooking and driving, the taxes and stuff are often imported from one particular country. So in Kuwait, there was a lot of like Bangladeshis and I speak Bengali, which is people in the east side of India speak that. So I spoke to all the locals in Bengali and I'd talked trash about all their bosses and stuff. And they'd always give me discounts on if I was trying to buy a fish or something for your notes, for the collections, or get a it's just funny speaking so much Bengali in this like middle Eastern country, things like that.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (18:02):

Another just funny trip, one last one. We're in the middle of the Amazon and we're on a boat called the Calypso which is the same name that a Jacques Cousteau's boat was. And it was a party boat. That's what it was called a Calypso. So the boat had basically a dance floor and a strobe light. And in the middle of the Amazon, we just play the loudest dance music every other night just because why not. And no one can hear you, you're in the middle of the river. And I just love remembering flashbacks of things like that. These tiny moments in the field of just unexpected joy once you survived other things and get to have some fun that's always really important for me.

I can't believe I get to get paid to do the stuff I get to do. Especially discovering, there's some fish I've seen, I'm just like, this is not real. I know we just pull this up. It was like, this is plastic. I remember seeing my first, I hope people look this up after, armored sea robin in Taiwan, it's just a big orange fish. And its head looks like a fake medieval mask or something, and it's bright red. What is this? There's no way people know about this. Because I would have known about it. It's just like one of those things.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (20:02):

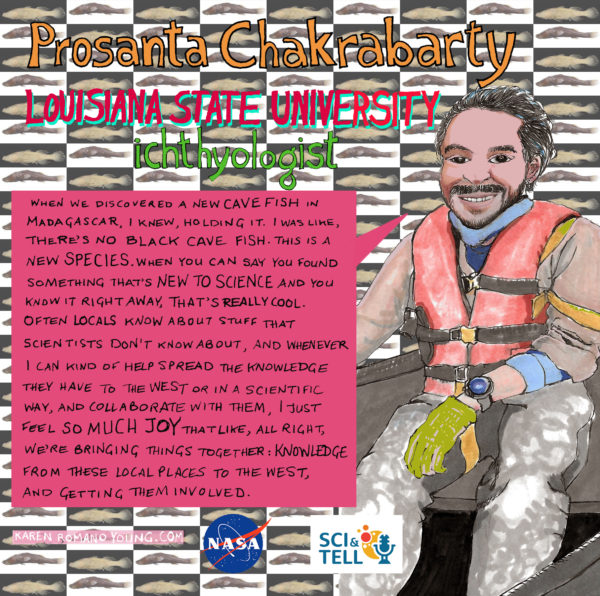

When we discovered a new cave fish in Madagascar, I knew holding it, I was like, there's no black cave fish. This is a new species. When you can say you found something that's new to science and you know it right away. That's really cool. Often locals know about stuff that scientists don't know about that are coming in and whenever I can kind of help spread the knowledge that they have to the west or in a scientific way and collaborate with them, I just feel so much joy that like, all right, we're bringing things together. Knowledge from these local places to the west, and getting them involved.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (20:48):

I have students from Guatemala and Cuba and traditionally have students from the places I work and it's just like a joy to be able to have that melding of different countries and their experiences. So yeah, all that stuff's just amazing that I get to do that. I'm just like shocked that's a job I get to do.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (28:03):

So a lot of the scientists they know that we just talk to each other, but we don't learn about the history of our field or about things that our colleagues in the humanities are working on. And I just like to see academia move forward with a more collaborative effort between groups like that. So I'm excited. I'm really excited about that. It's weird. It's a weird thing to do, a collaborative center like that, but I'm really excited about it put on some, some events and get people communicating between different parts of LSU and beyond. So I've had postdocs or artists have had students that had humanities interests. And I think this is a good way for us to sort of build a more interesting university. By having those collaborations between pretty widely divergent groups.

Paul Molin (29:28):

What do you think are the biggest challenges in science today?

Prosanta Chakrabarty (29:38):

I think that for me it's that science is sort of concentrated in rich Western countries. And there's just so much knowledge and expertise that we haven't tapped into outside. I see it all the time doing field work, were people often helicopter in and as soon as they say goodbye, they never think about those people again. And for me, it's like building scientific infrastructure abroad where you can go in and really collaborate, like truly collaborate with the folks out there and understand why they live and the way they do. And I think people's perceptions as some of the countries I've been to is like, oh, that's a third world country, they make a dollar a day. I'm like this person eats fish and whatever food they want every day. And spends all their time with their family and is living a great life.

Prosanta Chakrabarty (30:36):

They know they don't have an iPod and they don't have, I don't know if anybody has an iPod anymore, like an iPad, but they have what they need and what they don't have maybe is like access to higher education or to maybe the kind of healthcare that we have in the west. But other than that, they're like really content and they know a lot of stuff about the natural world that we just don't understand. And so for me, understanding and building that scientific infrastructure is the biggest gap that we have. We have to understand people better to make the science work better for everybody.

Nisha Mital: I’m from Florida, and I remember going on trips to the Everglades when I was younger. There are so many things to do there, but I one of the best things to do there is to take tours of the Everglades from people who grew up living there. They don’t have any fancy degrees, but they provide some of the most in depth and interesting tours I’ve ever been on. So I agree with Prosanta, there is so much knowledge out there that isn’t concentrated in a university setting, and I think science would really benefit from tapping into it.

Shane M Hanlon: Thanks to Prosanta for sitting down with us. And special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible, to Nisha for producing, and to Paul Molin for conducting the interview.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From these scientists in our respective home studio, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.