Paula Buchanan: Communicating Disaster

23 October 2021

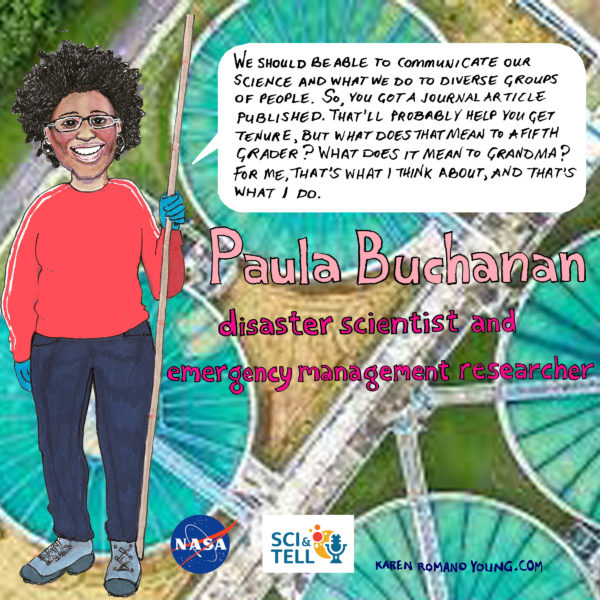

Paula Buchanan is a disaster scientist and an emergency management researcher. Her job is to help effectively communicate the science of emergencies and natural disasters so they can empower themselves to do something- for Paula, there is no point to science if it isn’t benefitting others.

In this episode, we talked to Paula about pivoting from science to social science, or as her dad says, being a “degree collector.” She also shares advice about persevering and setting boundaries as a woman of color in STEM, and how important it is to “meet people where they are” when communicating science.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and Nisha Mital, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: I’m from rural Pennsylvania, which means, I grew up on well water. I have a big family but by the time I came around, it was mainly just me and my parents. Still though, I guess old habits die hard because my dad would always say, “don’t take too long of a shower b/c the well will run dry.” I just thought he was being a dad and it was an idle threat. Well, it wasn’t. One day our well dried up. And I mean dry – there was just no more water. Turns out when your well dries up, you have to drill a new one. But that’s a process – folks need to come out, drill a bunch of pilot holes hundreds of feet into the ground, find another source, then put all the proper equipment in the ground. The whole process can take weeks, if you’re lucky, which we were. But in the meantime, we still needed water. And luckily, we had very generous neighbors. Now, we didn’t shower at their place or anything like that. We hooked up about a dozen hoses and ran them from their house to ours, through a woods over a few hundred yards, and for those couple weeks we both survived off their well. And while we got our well dug and got over this relatively minor inconvenience, I recognize that I’m in a super fortunate situation to not have to worry about access to water…

Everyone has a story, even, or maybe especially, scientists.

Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it.

From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: Alright, I’m looking forward to this one. Our interviewee today is a colleague who’s always a joy to talk to with some incredible stories. I’m gonna bring in Nisha to introduce her. Hey Nisha.

Nisha Mital: Hey Shane

Shane M Hanlon: So what do we got today?

Nisha Mital: On this episode, we interviewed Paula Buchanan, a disaster scientist and emergency management researcher. For Paula, there’s no such thing as science if it doesn’t benefit our communities, and that’s the mantra she has carried throughout her entire career. I’m excited to share this episode with everyone!

Shane M Hanlon: Thanks Nisha. Our interviewer was Paul Molin.

Paula Buchanan: (00:00)

I'm Paula Buchanan. I am a disaster scientist and an emergency management researcher. I research disasters. Across the world, it's usually called disaster management or disaster science. In the United States, we actually call it emergency management. So, that's why I always put disaster science and emergency management in the title of what I research to explain it to more people.

Paula Buchanan: (00:39)

So my research actually focuses on the people in those disasters. Quite often, there's an entire field of science called engineering where people look at how levies are built or how bridges are built. And if using that same scenario, I look at the people who actually use those bridges and dams and how you can actually more or effectively communicate with those people as to why that dam is there, how it can be useful. So, that's what I'm looking at, is how you can more effectively communicate the risk of different disasters, say a levy breach or a bridge falling down, how I can more effectively communicate with people from what's called like behavior science from the public health sector.

Paula Buchanan: (01:26)

Quite often in emergency management and disaster science, the people element of the equation is left out, but it's the people that use those systems and those bridges and those levies and those waterways that are built, so that's what I do. I focus on the people and how to more effectively communicate with them so they can actually empower themselves to actually do something.

Paula Buchanan: (05:36)

Well, I've always been interested in science and I am going to get a little kind of wonky here for a minute. There's kind of the bench scientists, like the biologists and microbiologists and the chemists that do all this fancy stuff in labs and lab coats. Then there's what's called the social scientists who are more interested in the people aspect of things. I, folk, I'm more of a social scientist now, but I did start out, unlike a lot of my fellow social scientists, as a bench scientist. I was a biology major. I always liked science. I always liked like animals. I was one of the few girls in the elementary school that thought lizards were cute. I thought they were adorable.

Paula Buchanan: (06:11)

But I didn't want to be a veterinarian and take care of animals, but I was interested in them. I think what really got me interested was just, in biology and chemistry class, playing with microscopes. I just think microscopes are really cool, looking at stuff, figuring out what's going on under the microscope. I think that's how I actually got into science. It's all the microscope's fault for being kind of this cool tool. That's probably it. Just an interest in it from the get go. As my family likes to say, my mom was smart, my dad was smart. So, it's no surprise that Paula likes being smart, nerdy and bookish.

Paula Buchanan: (06:51)

It's like, look, it's genes, it's nature and nurture at work. It does help being a little intelligent to go into science, but all kinds of people can go into it. There's actually entire citizen scientist movement, which I think is really interesting getting people out there, helping scientists, not as study subjects, so to speak, but as peers going out and doing the work that a whole bunch of scientists do. It's so empowering for people to get involved in science. Yep.

Paul Molin: (07:23)

Then when did you make that transition to social science?

Paula Buchanan: (07:26)

That's actually pretty recent. As my dad calls me, I don't mean to be a degree collector. It just so happens that I pivot my career and I'm inspired by different things. But I started out in public health, which like emergency management disaster science, more practitioner based. I think, and then you'll hear this from a lot of people who are in the emergency management and disaster science space, I think I was drawn to the area, but didn't know it existed. Public health has been around for a couple centuries now. If you're a biology major, it's pretty easy to transition into public health because they are related.

Paula Buchanan: (08:10)

But as its own academic practice, emergency management disaster science are very new. For example, you don't find departments of emergency management. You'll find, say a department of public affairs or political affairs that has some disaster scientists in it. Or you'll find some geographers who do all these really cool things with maps who focus on disasters and mapping them. I will say there wasn't any one disaster that made me think of this is what I want to research, which is pretty common in the field. There's a personal connection to a lot of people in my field and why they pick what they did. I found it and didn't even realize I was looking for it.

Paul Molin: (12:42)

So many people, they go to school, they study something and then they end up in a career and they just stick with that career for better or worse for their rest of lives. There's risk, I guess, in switching in these right turns you've taken along the way. What has your mindset been as far as like, all right, hey, this is different, this is a change, this maybe there's a risk, but you want to see it out?

Paula Buchanan: (13:15)

Well, I will say graduating from Tulane, living in a city like New Orleans when Katrina happened, that's like one of those watershed moments in the entire field. I will say not just myself. I think a lot of people actually decided to transition eventually after what happened with Katrina. I will say, and I think I'm like my mom in this standpoint, I'm very much a lifelong learner. I'm not one of those people that thinks, because I have my terminal degree, or even if I have my bachelor's degree, that I'm smart.

Paula Buchanan: (13:48)

I know a lot about one thing. I'm academically proficient to use some fancy words there in one area. That does not necessarily make me smart. I think that's one thing that we get wrong in academia, is we think, because we have a PhD or equivalent terminal degree, that we know it all, and we know it all about one thing. The world is made up of all kinds of things. I think that's where we, as academics, get some things wrong.

Paula Buchanan: (14:16)

We should be able to, for example, communicate our science and what we do to diverse groups of people. So, you got a journal article published. So what? That's my big thing, is like, that's great. That'll probably help you get tenure, but what does that mean to a fifth grader? As I was saying in a presentation last week, what does it mean to grandma? For me, I think that's what I think about and what I do. Because I am doing research in a field that I didn't know that much about, emergency management, I basically got my boots on the ground, as they say, in the field, and I completed what's called CERT training.

Paula Buchanan: (14:52)

It's a community emergency response. I can't remember what the T stands for. I think it's maybe T. But it's basically a way to empower people in the community with this training that allows us to be able to triage patients until the EMTs get there. How do I set someone's arm with a blanket or a sheet? How can I help the emergency response teams and police and fire that are coming in until they can get there? Because there is a delay. I did CERT training. I also participate in what's called Citizens Fire Academy, which allowed me to go through just a little wee bit of the training that firemen and EMTs actually do.

Paula Buchanan: (15:42)

I got to wear, what's called the turnout gear, which is about 30 pounds. I put the oxygen pack on my back, which is about another 30, and I just teetered backwards. You can't see me because I'm just talking, but I'm about five foot tall and I'm pretty tiny. That gear, in the deep south in Atlanta, in August, was heavy. But it made me walk a little bit in the shoes, in that turnout gear, that firefighters do every day of their lives when they're to just be able to empathize a little bit about what they do.

Paula Buchanan:

The way I usually explain it is that I have all these different tools in my toolbox. If I had stayed and gotten like a PhD in biology and a master's in biology, I would have a hammer in my toolbox, and it would be a fine-tuned high end titanium based hammer.

Paula Buchanan: (17:20)

It'd be fancy. But instead, I have a hammer, I have nails, I have a screwdriver, I have a Phillips, I have a flat hat. I actually do know the difference between those two, which a lot of scientists don't. I have different kinds of screws. I have needle nose pliers and the other kind, which I can't remember what they're called, but I have all these different tools in my toolbox that I can use. I think it's more preference.

Paula Buchanan: (19:04)

Well, I will say, as, I guess people can't see me, but I am a woman of color. I am a black woman, and I did start and the biological scientists, or the bench scientists, as they're called, as a whole. It's changed now, but you used to not see a lot of women of color, specifically black women on the bench. You really did not. If you did see us, we were usually processing specimens for someone else to actually do more work on later. I will say that, that's probably been one of the biggest hurdles is, I'm a black woman and I'm very proud of that, but I think what's been hard for me are the hurdles that other people have dealing with that fact.

Paula Buchanan: (19:44)

For example, looking at my CV, or my resume, and assuming that I am not a person of color. That it's pretty obvious I'm a woman by my name, and I am cisgender, so it's pretty easy to recognize, but just ... I've actually, and this has happened multiple times in my career, where people have seen my resume, haven't seen me, I walk in the room and jaws drop. That happens multiple times. You just have to that. It's not about you. It is about them. It's their issue, but that can make it so you might not have as many opportunities as you might have.

Paula Buchanan: (20:21)

But I've never let something like systemic racism or discrimination hold me back. But I will say it is very frustrating to see people who are more kind of on the mediocre side of things, but don't look like me, who get the jobs. That's very difficult to deal with, but I think that all people of color have to deal with that. So, you just chalk it up as ... I have a jazz singer, I have a cousin who's a jazz singer in the Netherlands. She always used to tell me, "Remember this Chinese proverb, fall down seven times, get up eight." And that basically says it all.

Paula Buchanan: (21:01)

Yeah, get up those eight times if you fall seven, and realize that a lot of times those falls or those failures aren't because of you, it's because of others that want to, for whatever reason, get in your way of succeeding, as opposed to helping you go down the path of success.

Paul Molin: (33:41)

I realize this is kind of an unfair question I've been asking people, but work-life balance, how does that fit into the science community for you?

Paula Buchanan: (33:50)

Oh, that is not an unfair question. I always tell people, where I used to teach for over 10 years, I was the only staff, not even faculty, of color. Even the maids were white. I was it. Students would actually just stare across the hall into my office like, wow, there's the unicorn. It was just really sad. I can attest that women, especially, and also people of color, one thing you have to learn to say in academia is no. That's the most powerful word, and that's where I get my work-life balance. I will definitely tell someone, no.

Paula Buchanan: (34:30)

People would be like, oh my God, we need you to come to this diversity luncheon to represent the university, and this diversity dinner, and the president's house for that. They'll be having you run ragged while you're still doing the rest of your job, and so you have to be able to say no. That's my main thing is, I don't have meetings on Mondays or Fridays. There's got to be a really good reason, say you're abroad, in another time zone. All my meetings are on certain times and certain days of the week.

Paula Buchanan: (35:02)

I will tell people, I do not meet on Mondays and Fridays, you have to understand that with me. Because those are my days for doing research and catching up with anything that I forgot with being busy for the rest of the week. Yeah, a work-life balance is very important, and I do wish that, in academia, more of us would learn how to say no. Just maybe do it more politely than some of us do, but just, no. That's how I do it. That's how I maintain work-life balance.

Paula Buchanan: (28:30)

Informatin is power in academia, and also is money. Things can be your intellectual property, and unfortunately, we don't care to share that stuff a lot. My science is all about sharing. So, it sounds really hokey, but sharing is caring and vice versa. I like working with people because you can learn so much from them. No offense to we, people in academia. We all are, for better or for worse, a certain type.

Paula Buchanan: (29:11)

A lot us don't have experience working outside in what I call the real world, which is outside of academia, and I've done that. I do have a different take on the research that I do. Now, do I love also just looking at some roles of an Excel spree, coding data? Yeah, I like doing that too. But it's always thing to hear from people, different perspectives that you didn't think about that can impact the research that you do and why you do it.

Paul Molin: (29:40)

When you think about what you do in disaster management, what are the biggest challenges right now? Because it seems like, every time you turn on the news, there's a disaster at this point, right?

Paula Buchanan: (30:01)

Yes. The biggest challenge in my opinion is, and this goes back to meeting people where they are as opposed to where you want them to be, is for people to understand and to accept that we all have a role in this stuff. There's probably, where Dr. Hayhoe is, there's probably entire areas of the State of Texas, for example, you can't even climate science at a public meeting. People will just walk out. That's why I really love the work that she does because she frames it in a different way.

Paula Buchanan: (30:33)

For example, I'm looking at water, specifically drinking water. So, what I ask people is, have you noticed your water bill's gone up? Why do you think your water bill's going up? Are your pipe pipes clogged? What is it that you might be you doing and how can you improve it so your pipes don't get clogged? Now, those might seem really small, granular things, but they are related to climate change because we are losing the amount of water that we have because of climate change. But do I mention the phrase climate change to them? No, because that's not meeting them where they are. It's meeting them where I think they should should be.

Paula Buchanan: (31:09)

That's very presumptuous of myself as a scientist. I think that communication is hard because scientists have a tendency to wave their finger, and politicians do it too, in our faces and tell us, this proves climate change is real. Yeah, I know that, but there's facts and then there's perceptions, attitudes and beliefs. And a lot of times there's a gulf between those two camps. Don't do the finger wag or the finger wave. Just talk about, hey, what can you guys do to help a wildfire, say in the west coast, like jump from top of valley to a top of valley? Which is a huge issue.

Shane M Hanlon: This is how I live my professional (and probably should be how I live my person) life. Paula has a great point - we , usually, need to understand why people believe what they believe before we try to change their mind on something. That’s great advice and I wanna thank Paula for talking with us. Special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible, to Nisha for producing, and to Paul Molin for conducting the interview.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From these scientists in our respective home studios, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.