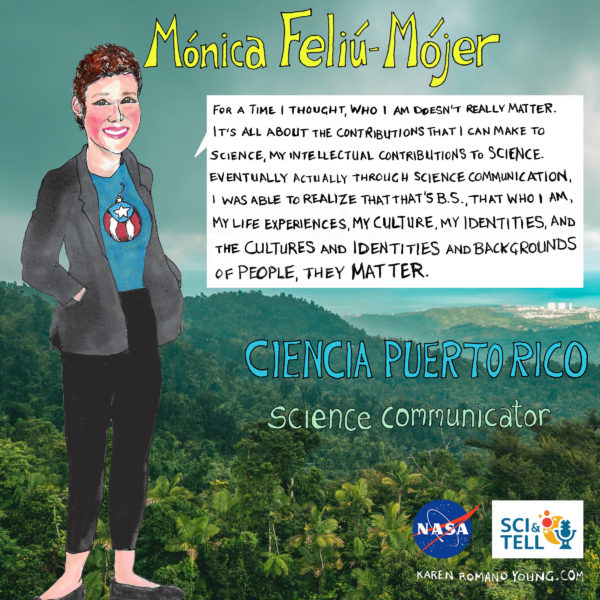

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: Making Science More Equitable and Inclusive

07 June 2021

A big part of Mónica Feliú-Mójer’s life mission is to help use science communication as a tool for equity and inclusion, and she has certainly achieved this working with two non-profits called Ciencia Puerto Rico and iBiology. Mónica has spent over 15 years making science culturally accessible to different communities in Puerto Rico, and she is eager to continue building those relationships throughout her career. We talked to her about the “scientists without a title” she grew up around in rural Puerto Rico, work-life integration (not work-life balance), and how your cultures and identities absolutely matter in science, despite common belief.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: I went to college to be a science teacher. I ended up working with a grad student in, frankly, terrible field conditions. Picture me counting the number of plants in open fields, under a blazing sun, air so heavy with mosquitoes that I could swim through them. Despite this, I was weirdly hooked on research. I decided to ditch high school and become a science professor. I went to grad school and did pretty well. Got grants, did research, taught, all that jazz. But something was missing. I was doing conservation research but I didn’t know where the results were going. Did it matter? Was I making a difference? I got my PhD and then switched my focus from doing science to explaining science. I did some policy work, a little bit of outreach, and landed where I am now at AGU as a scientist who teaches other scientists how to tell stories and communicate science to non-scientists. Science communication matters – it’s partly why I’m doing this podcast – and I hope that other scientists do too.

Shane M Hanlon: Everyone has a story, even, or maybe especially, scientists. Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it. From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: Today we’re taking a break from hard science to talk about communicating. And I couldn’t think of a better person to chat with than our next guest. Our interviewer was Paul Molin.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: My name is Mónica Feliú-Mójer. I am a scientist by training and a science communicator by train, and my work focuses on using science communication to make science more equitable and inclusive. Right now I do that working with two non-profits called Ciencia Puerto Rico and iBiology. Broadly I do anything from training scientists to do effective and inclusive science communication, to producing videos and documentaries, and producing all different types of multimedia content to communicate science in more inclusive and equitable ways.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: My focus is on effective science communication at all different levels. I like to think about my work, particularly my work in training scientists and building their capacity to communicate effectively, as giving them a toolkit that they can adapt to different scenarios. So that they can be effective communicating their ideas when they're asking for funding, when they're finding collaborators, when they're finding a job. But that they can also be effective when they're communicating with people who are not experts, who are policymakers or educators. And so I try to focus on the process of effective communication with a particular emphasis on how to make sure that that process is also inclusive of different people, different cultures, different levels of expertise. But in terms of... When I think about the products that I'm often creating, my focus is on communicating science to non-experts, particularly to populations that have been historically marginalized by and from science.

Paul Molin: Why is it important to be able to effectively communicate to those populations that have been marginalized, or people who don't speak science?

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: I think there's several reasons. First, there's equity. The fact that there some populations like I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. Broadly, if you think about people who speak Spanish or Latinx, though they have been historically marginalized, even abused and oppressed by science. And so there is an aspect of equity, of correcting some of those historical inequities and exclusion. But there's also more practical things. If we take the COVID-19 pandemic, it has disproportionately impacted Latinx populations in the United States. And unfortunately when you look at Latinx people who speak Spanish, whose English is not their first language, there're lower levels of health literacy. They know less about health topics, or there're... Because they have less proficiency with that kind of knowledge, it means that when they go to the doctor, they don't have enough information to be able to ask the right questions to their doctor about, is this medication going to have a side effect? When should I get vaccinated, those kinds of things.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: And that lack of information that, that population faces has direct impact to the decisions that they have to make about their health, about the health of their loved ones. And so because there is that lack of information, it means that a population that's already vulnerable, it's going to be even more vulnerable in a situation like a pandemic. And so there's a good part of my work that is focused on Spanish language science communication. And not just making sure that information is available in Spanish for Spanish speaking populations, but that it also culturally translates. That the information is presented in a way that is relevant to the culture, the context, the realities, in my case of different Puerto Rican population. So that they can take that information and act upon it, use it to make decisions about their health, about how they are going to protect each other and their communities.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: Right, yeah. I mean, I think when you connect science to people's culture contexts, their values, their life experiences, identity, the things that matter to them.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: I think coming in with, I'm going to respect you as a group, as an audience. I'm going to understand where you're coming from, who you are, your historical relationship with science. When you look at populations that have been historically marginalized, they have been abused by science. We can't deny that. And so when people say, I am not sure that this vaccine is safe. I've heard a lot, I've been doing a lot of work with different marginalized communities in Puerto Rico to promote COVID-19 prevention. And when it comes to vaccines, their main concerns are, is it safe? Was it developed too quickly? What are the ingredients? Is this going to actually get to people like me? Is it going to reach my community? And when it comes to, is it safe? What are the ingredients?

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: Early on we heard a lot about, and this is mostly part of my work with Ciencia Puerto Rico, we heard a lot about, are they experimenting with us? And if you look at the history in Puerto Rico, the birth control pill was tested on Puerto Rican women without their consent and without their knowledge. So historically, if you look at what's happened with science and medicine in Puerto Rican populations, it is not a surprise that they're like, well, am I being experimented on? And so I have to take that into account and think about, and respect that. Respect that there is a mistrust and then work with those populations to say, I understand where you're coming from, I understand your concerns, here's how I can put the knowledge that I have about science and put it in your service.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: I grew up in a very rural remote community in Puerto Rico working class community, and so I was surrounded by science. I grew up in basically a farm with a bunch of animals and so my environment was the first thing that got me interested in science. I was always, since I was very little, I was into building things. I was into living things. I was into biology. I wanted to understand how living things worked. But I didn't necessarily know that I could be a scientist. The role models, the references that I had about what being a scientist was, or what doing science looked like, were very foreign to me. They mostly came from TV, and all of the science shows that I used to watch were produced in the US. They were originally in English dubbed in Spanish and so even the Spanish that they were speaking didn't really sound like my own, it was that generic Spanish.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: And of course, many of them they didn't look like me, they didn't act like me. And even in school, I was often learning about the historical figures, Einsteins, Marie Curies, that kind of thing. And so I didn't have those references of science was being done in Puerto Rico, science was being done by Puerto Ricans and so I didn't know that I could be a scientist. But I was very fortunate to be encouraged, that science interest was always encouraged by my parents. And now as an adult, I've realized that this perception that I didn't know scientists was actually not quite true.

Paul Molin: What was it like to go from an undergrad in Puerto Rico, where you didn't really know until pretty late in your undergrad, that you could even make science what it became for you. To go into these schools that are known for science and being surrounded by people who have been on this trajectory their whole life. Was there an overwhelming aspect of it?

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: Yeah. It was a shock. It was definitely a shock. I mean, the lab where I was a technician at for three years, just that lab was twice the size of the entire department, where I did my undergrad research. And so it was a shock at multiple levels. When I made this move, it was the first time that I lived away from my friends and my family. It was a shock because of the language. English is not my first language, Spanish is my first language and so I had to go from speaking Spanish all day every day to speaking English most of the time. The weather was certainly a shock. But also the culture, the institutional culture was different.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: [B]efore moving to the US I was always very proud of being a Puerto Rican scientist. As a scientist, that was my main identity. And then after I moved to the US I felt like I had to suppress that, my Puerto Ricanness. I felt like I needed to be a scientist first and foremost, then that it shouldn't really matter what my identity is, those things shouldn't really matter.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: And that caused an identity crisis for me. Because I had always been so proud of this and for a time I thought, who I am doesn't really matter. It's all about the contributions that I can make to science, my intellectual contributions to science. Eventually actually through science communication, I was able to realize that that's BS. That who I am, my life experiences, my culture, my identities, and the cultures and identities and backgrounds of people, they matter. They inform how people approach science, how they approach their work and that it is important that we recognize the value of those. And that people are able to bring those into their work and into how they do science. Because that diversity of far and of experience really enriches the scientific enterprise.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: I think I may be the only person or one of very few people to be accepted into my graduate program twice. So I started my PhD in 2007, but that wasn't the plan. The plan was I would start my PhD in 2006. And I had originally decided that I would go to Stanford to do my PhD. In the end it was between Stanford and Harvard, which are, I mean poor me, right? They were both wonderful choices and I decided I'm going to go to Stanford, I'm going to be adventurous. Even though at that point in my life, moving to the West Coast was very scary. It was very far from home and I was like, screw it, I'm going to do it anyway. As I was getting ready within that year, 2006 and 2007, my father had a mental health crisis. He suffers from bipolar depression. And he had a pretty severe crisis that put everything on hold for me. I had to go home to manage that with my family.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: And then once I came back to Boston, I was like, is going 3000 plus miles away from my family the thing that I need to do now? And so I actually chose to defer grad school at my admission, so basically push it back a year. And then in that time I realized I can't move that far. I'm not going to stop from pursuing my dreams, but I can't move away that far. So I actually went through the grad school application process a second time, because I realized I needed to stay in the East Coast, that I did. I ultimately wanted to go to Harvard for my graduate program and I had to reapply, I had to talk to all these people. Program coordinators and directors and be like, I said no, but actually backseat please. Here are the reasons why I think, I basically made a mistake in saying I was going to go to Stanford, but what I want is to really go here. And these are personal reasons, not just science reasons. But there are personal reasons why I want to stay here and I need to stay in the East Coast.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: And so I was fortunate to have their support, and even though I had to go through the process again, I eventually was accepted a second time. And I did decide to go to Harvard for graduate school. I think you're right, when you just look at the things that are on my CV, it gives the impression that it's that storybook success, like success has been linear. which I think is what a lot of people have the perception. When you have all these accolades, it's like, oh yeah, you went from one thing to the next, but you're not seeing all of the hard work. You're not seeing all of the blood, sweat and tears. You're not seeing all of the failures that people go through to get to that success.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: The biggest hurdle. I mean, it's not singular, I will say. I think one of the biggest hurdles for, not just for me, but for people with my background is that we don't have access to the implicit rules of, in my case, of science and academia. That you're supposed or expected to fit certain boxes, or write things, or say things in a certain way. That you're supposed to have certain experiences that then make you competitive to say, complete a PhD in an Ivy League. I think now I do a lot of mentoring of undergraduate and graduate students in particular. And one of the things where I feel I can help them most is in navigating those implicit rules that nobody teaches you.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: I am most proud of the 15 years plus of science communication work that I've been doing in Puerto Rico. This work really started... I stumbled upon science communication. I didn't know that science communication was, just like I didn't know that I could be a research scientist. I didn't know that science communication was a career that I could pursue. I stumbled upon it 15 years ago, when I started volunteering with Ciencia Puerto Rico, which is one of the non-profits that I work with right now. This is a community that brings together people who are interested in science in Puerto Rico, and taps into the collective knowledge of that community to create social impact in Puerto Rico, through communication and education, and supporting the professional development of scientists and their civic participation.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: So I actually don't like to think about work-life balance. I like to think about work-life integration. I feel like balance... I don't know, it fosters this idea of things are perfectly balanced or perfectly equal or equalized and it's not-

Paul Molin: It makes work the bad guy too, right?

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: ... Yeah, and honestly doesn't fit my reality. And so I think about integration. Integrating the things that are important to me and in my case, my work is very important to me. I see my work in using science communication as a tool for equity and inclusion. It's part of my life mission to be quite honest. It is at times hard for me to shut that part of my brain down and be like, okay, I'm not actually going to do work. But something that's equally important to me is my family, and my friends, and my loved ones, and spending quality time with them. And so I think about how do I integrate all those things that make me feel whole as a human being. And I recognize that there are going to be times because of my work demands or the demands of my personal life, where I'm going to have to put more time and energy into spending time with my family and connecting with my loved ones.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: And then are other times where I'm going to have to spend more time and energy thinking about work. But I also try to be intentional, and this is constant work for me of setting boundaries, of understanding you are working too much and you are feeling burned out, and recognizing that and setting the boundaries. Because especially for my work, sometimes the urgency of addressing the inequities that I see, they feel heavy. It feels like there's so much to do, and there's so little time, and there's so many things I have to fix that it can be really overwhelming at times. But I've come to understand that setting those boundaries and taking care of myself is an important part of the changes that I want to create in the world. Because if I'm not healthy and I don't feel whole, then I am not going to be able to do the heavy lifting, the heavy work, that's going to be required of me.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: I love to cook to disconnect from other things and clear my mind, and I try to make sure that I make time for that and also especially during this pandemic. I used to go to Puerto Rico three or four times a year for work, but also to visit my family. Most of my family is there and it's been more than a year since I've seen them. I've been trying to make sure that I'm connecting with people on the phone or video conferencing to make up for that, until I'm fully vaccinated and then we can travel again and I can go see them and hug them.

Paul Molin: That'd be awesome.

Mónica Feliú-Mójer: Yes, I'm very much looking forward to that.

Shane M Hanlon: As of this recording, I received my second dose of Pfizer yesterday. I am literally counting down the days until I can hug my parents again, so I know the feeling, and want to thank Mónica for taking the time to chat with us.

Special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible and to Paul Molin for conducting the interview.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From this scientist in the studio, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.