John Mather: Big Bang Mapper, Nobel Prize Winner, and James Webb Scientist

09 August 2021

The James Webb Space Telescope, which is the planned successor of the Hubble Space Telescope, is set to launch this October. I don’t know about you, but we here at AGU are very excited!

We were lucky enough to talk to John Mather, the senior scientist for the James Webb, on our latest Sci & Tell episode. We learned about his journey to becoming a scientist, and he even talked to us a bit about James Webb’s capability. But if you think the telescope is the most exciting part of his career, guess again- he previously won a Nobel Prize for mapping the Big Bang. Listen to the episode to learn more about John Mather, the amazing projects he has worked on, and his experiences with sudden fame!

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and Nisha Mital, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: A couple years ago I was at a social event for AGU with some members and staff, just bullshitting with folks over cocktails. I honestly don’t even remember what I was talking about, but I do remember hearing over my should, “Hey, I recognize that voice.” I turned around and a stranger was standing there, with a quizicle look on his face. I asked him “Have we met before?” In that moment I could see the realization in his eyes, like a figurative light bulb going off in his brain. He said, “NO, but, I do know your voices from Third Pod from the Sun” (which is another AGU podcast I co-host). And I gotta be clear, this is not a common thing for me – Third Pod gets a decent amount of listens but I am by no means famous, or even well-known outside of certain science circles. And while the moment was fleeting, it did feel kind of good…

Shane M Hanlon: Everyone has a story, even, or maybe especially, scientists. Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it. From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: Alright, today we’re back to NASA and we were honored to talk to a Nobel Laureate. I’m gonna bring in Nisha to introduce this one. Hey Nisha.

Nisha Mital: Hi Shane

Shane M Hanlon: OK, can you give us a little preview of our next interview?

Nisha Mital: Sure. On this episode we talked to John Mather. He’s currently the senior scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to replace the Hubble this October. We got to talk to him about winning the Nobel for mapping the Big Bang, and about all the work he’s doing on the James Webb.

Shane M Hanlon: Great, our interviewer for this one was Paul Molin.

John Mather: So I'm John Mather, I work at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. I'm senior scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, which is the planned successor for the great Hubble Space Telescope and it is planned for launch in October of 2021.

Paul Molin: Exciting things on the horizon.

John Mather: Yes, indeed.

John Mather: What drew me to science? I think the first things that I remember have to do with science just about. I remember in probably kindergarten or first grade, I must have heard about infinity. So I remember covering an entire page with zeros to show that there was no largest number. So I was really little when things started to get interesting. By third grade, my parents had made sure that I was exposed to Galileo and Darwin. They had gotten biographies of these folks and they were reading them aloud to myself and to my sister. They had taken us down to the Museum of Natural History in New York so we saw the planetarium show and the bones and the volcano exhibits and I thought, "This is so cool. How could I not be interested in this?"

John Mather: And then as time went on I got various science toys to play with, a little crystal radio, a one tube radio eventually. Then I started saving up my pennies to get telescope parts and build things at home. So I got started really early. I was just about the only science kid in my school though. The location was very rural northern New Jersey far from the city and close to the Appalachian Trail. So it was farm country but my situation was unusual because I was living on a research farm belonging to Rutgers University. And so my dad was a scientist and he was working on dairy cows, try to get more and better milk from those cows. And so I heard about genetics, I heard about statistics, I heard about those lab techniques when I was pretty little.

John Mather: All though I did not get excited about doing it myself. I thought somehow relativity, astronomy, quantum mechanics, all those things that were just coming over my horizon, they were really exciting. And even much more mysterious than cows.

John Mather: [A]t Berkeley I wanted to be like Richard Feynman, he was my hero as a scientist because he thought so well and explained so well about quantum mechanics, I loved his books, I loved his talks.

John Mather: And so I'm going to be like Richard Feynman. But then I got tired of that and also I said, "Okay, faculty, what should I do?" They said, "Unless you're rich, don't do that because there are no jobs for other people like Richard Feynman. There are just no jobs." So let me try something experimental, so I went around and interviewed faculty members to see what are they working on. So I found Paul Richards and Charles Townes and they were working on measuring the Big Bang. So how do you measure the Big Bang? Well you measure the heat that's left over from the beginning.

John Mather: So, "Okay, we'll try this." So I got started in that and started working with other people that were already building some experiments to do this. So then we went on from there and of course we tried the first experiment on the ground from a mountain in California and it worked eventually. It was scary because we had to get helicopter ride to a 12,000 foot elevation. Oh, that's hard work and actually those helicopters crashed once in a while but not with me on them so I was lucky. And so that one worked but it wasn't interesting.

John Mather: So the next project was created by my thesis advisor, Paul Richards, and it was much more ambitious. It said, "Let's build an apparatus to send it up on a balloon to a high altitude and measure the Big Bang radiation from there." So that was my thesis project and we built it and we launched it and it did not work. So that was my first big failure in school, thesis project did not work. So what am I going to do? Well, Paul let me finish my thesis about the first experiment that did work and the second one that didn't. And he let me out and I got a job at Goddard Institute for Space Sciences in New York City. So that's a NASA laboratory.

John Mather: So I thought, "Well, I'm just going to give up on this cosmic background stuff. It's too hard." And then a totally remarkable thing occurred and NASA announced opportunities to write proposals for new satellite missions. So that was just five years after we first landed on the moon but we were clearly not going to do moon landings forever so what else are we going to do? Let's do some science. So I said, "Hi, boss, my thesis project failed but we should try it in outer space." So he said, “Okay, we'll call up our friends and we write a proposal."

John Mather: So that was my idea and it grew. So how did that work? Well lots of writing, lots of talking, lots of meetings. Talking, writing, meetings, talking, writing, meetings, day after day, week after week, year after year actually. Until finally I moved down to Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland when we had an opportunity that we thought really might work. Maybe NASA would really fly this project. So by then I am, let's see, 30 years old and suddenly it looks like NASA is going to do my idea. Oh wow, this is exciting but I'm scared to death because I do not know how to do such a big thing.

John Mather: But NASA, of course, is pretty smart about these things and they said, "Okay, we're going to hook you up with an experienced team of engineers and they know what to do. So you talk to them and figure out what you need and we'll work it out." So we did. And after a lot of trouble and a lot of changes, it did get launched 15 years after our first proposal. So that became the Cosmic Background Explorer satellite and it went up in 1989 and immediately made discoveries. Six weeks later we got a standing ovation for showing a spectrum to the astronomers. So, oh my gosh, this was more important than I ever knew.

John Mather: And a couple of years later we got worldwide publicity for making a map of the Big Bang. So how do you make a map of the Big Bang? Well you measure this cosmic heat and see how bright it is in every direction. And our pink and purple and blue blob maps were all over the newspapers for a long time. And the phone rang every day for a long time about this. So these were the two big discoveries that propelled us to go off to Stockholm in 2006 and I got a Nobel Prize. So those were pretty exciting days. So that's mostly how I got to be where I am now. A very long and interesting process of taking an idea and writing it to launch and then eventually to a Prize. Conversely, it's a long distance between the idea in 1974 and the Prize in 2006, that's 32 years. So by then you're already off and doing something else.

John Mather: Well the thing that sort of surprised me the most was what it's like to be famous all of a sudden. The day that I got the call from Stockholm, it's a quarter of six in the morning here in eastern time, within an hour there were balloons on my front door, the photographers were there, I had just barely had time to have a shower and put on clothes. The phone rang perpetually for a long time. So suddenly you're famous and what are you going to do? So you try to put on your best performance and not say anything stupid because now the entire world is watching you. Then it gets even more intense when you finally go to Stockholm because when you get off the airplane, you are met by a diplomat and whisked off in a special car to a special waiting room and you're sitting there waiting for your suitcases to arrive and looking at a one foot high pile of Nobel Prize medals in chocolate.

John Mather: So of course you eat some. And then you get taken off to your hotel and gosh, you can't go in because there are people trying to get your autograph. They make a living getting autographs and selling them so you have to do it a little bit. But at that point I just want to go find the bathroom and go to sleep. So this is a reminder of how it's not all that great to be famous. And then of course the celebration goes on and on, it's 10 days of parties and speeches in Sweden. And there's no way you can prepare yourself for that sort of feeling. It just goes on and on and it's really intense.

Paul Molin: It sounds like it was probably a good 10 days.

John Mather: Yes. I enjoyed it. And I also had the feeling I have to be on my best performance, again, because everybody's watching. I have to do a good talk, I have to thank everyone. And of course there are little things that I miss like I traveled across the Atlantic without a tie, so I need a tie. So I had to borrow a tie from my friend, the Swedish diplomat. Then I went and bought one.

Paul Molin: It's amazing. We've done, obviously, several of these interviews and one thing that is a constant theme for people who are successful in the fields of science is that the self drive, the self motivation, the ability to be told no a few times and still push through. Can you kind of quantify how important that is for somebody who is looking at science as a career or has it as a career?

John Mather: Well, to tell the truth, I am not all that courageous. I've found that our idea was supported by management, by upper people, for a long time. It wasn't just us being courageous, it was other people thought it was a good idea. And so when you're lucky, you have a good idea that other people want you to do. And so even when there are setbacks, even when the space shuttle blows up and your rocket launch is going to be changed, you have to rebuild the whole satellite. Even disasters happen, people say, "Well, you know it was a really good idea. This is only way we have to get this scientific information so let's figure out how to make it go." So when you're a team, it's never all that personal. And so the team can have courage because we all have courage.

John Mather: I think I am most proud of having an idea that grew into a team project that could discover something really important about the Big Bang. So having an idea, that's cool. But getting the chance to grow with the team and make it come real, that's even more important to me. Knowing whereI started from as a kid from the country who hardly spoke to anyone as a child and growing into a member of a giant team with 1500 people that worked on that project and being able to say, "Yes, we did this together and that I contributed to the leadership of this process," that really feels good to me. So when I went off to see the king of Sweden, I got to say, "Thank you very much. We always knew that our project was important. Now you know and everyone knows. So we thank you."

John Mather: Oh absolutely. Right now I'm part of the team building the James Webb Space Telescope. We have a few hundred scientists and a few thousand engineers and technicians and managers. So the scientists say we wish for this and we have our ideas about our part to do with it and then we say, "Please help us build this incredible thing." So right now, for example, the whole observatory has been assembled. It has just been taken off the shaker which simulates the vibration of going up on a rocket. We are in a process of unfolding it to see if it really survived the simulated launch. We hope that it did and if it didn't, of course we have to figure out what to do but we hope that it did. And so that is all hands on work, it's incredibly detail oriented.

John Mather: [W]e have 12,321 little fasteners that all have to be tightened up to just about exactly the right tightness. Well, gosh, that's a lot to keep track of. If you were to ask an ordinary person to do that, they'd never do it. We have to have a system, we have to have trained people, we have to follow through on everything and we have to check our work. So I'm just telling you what it takes to go from, "Gee, I wish we could see an early star or a planet around another star," to, "We built the thing and now please make it work," is years and years of effort, thousands of people.

Paul Molin: When the James Webb goes up, what are you most excited about its potential?

John Mather: I am looking forward to something that we don't know is there that Webb Telescope is so incredibly powerful that I feel sure that something is there that we never imagined. So just to give you a sense of how powerful it is, if you were a bumblebee, one square centimeter at room temperature hovering out at the distance of the moon away from the telescope, we would be able to find you. So that is so incredibly shocking that I had to calculate it myself. But it's true. And so I'm sure there are things hiding out there that we don't imagine. So where could they be? Well it could be something that happened very early in the universe where all of those things that happened then have all disappeared because they've all been swallowed up into something else.

John Mather: Or it could be something still hiding out there now that we won't be able to find. For instance, recently we've discovered that there are lots of loose planets, rogue planets we call them, that have been expelled from the stars where they grew and they're just flying through space all by themselves. So we know they're there, nobody's ever seen them. We've only detected their presence. So this sort of goes from the extremes of the first things after the Big Bang to the nearest by little things. And something will turn up, I think that'll be exciting.

Paul Molin: That's awesome. What words of advice do you have to people who want to get into the sciences, are just starting out their science careers, what do you tell young people as they start off on a journey that may or may not resemble yours?

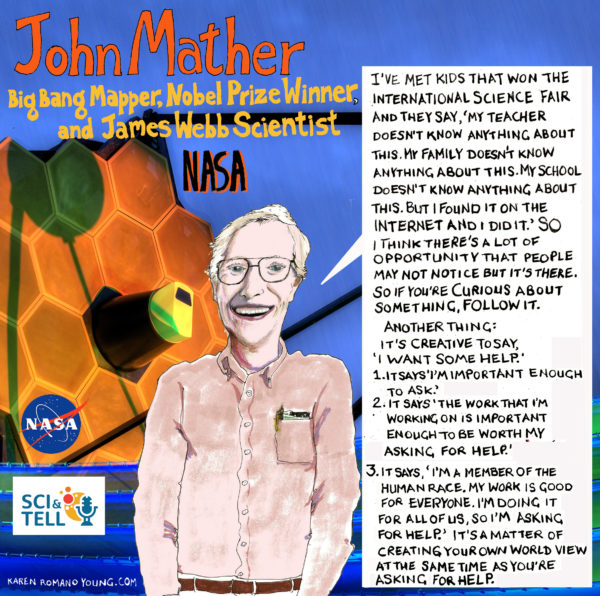

John Mather: Oh goodness, I think be curious. If you were curious as a child, if you liked to turn over rocks to see what's under them, if you like to go around the corner to see what's over there, just that can be science. We are built to be curious and so let's do it. So if you're curious about something, follow it. That's my thought and these days, even if you're not in a place with a big fancy school, you can learn everything you need, almost, on the internet. I have been to the International Science Fair a few times and I've met the kids that win and they say, "My teacher doesn't know anything about this. My family doesn't know anything about this. My school doesn't know anything about this. But I found it out on the internet and I did it." So I think there's a lot of opportunity that people may not notice but it's there.

John Mather: The other thing I would say ask for help. It's a very creative thing to say, "I want some help." Because, number one, it says, "I'm important enough to ask." Number two, it is, "The work that I'm working on is important enough to be worth it." And number three, "I'm a member of the human race and this is good for everyone. So I'm doing this for all of us so I'm asking for help." So it's a matter of creating your own world view at the same time that you're just asking for help. So it's much more important than it seems.

Shane M Hanlon:

Thanks to John for sitting down with us. And special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible, to Nisha for producing, and to Paul Molin for conducting the interview.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From these scientists in our respective home studio, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.