Dante Lauretta: The Wait for a Billion Dollar Space Sample

04 October 2021

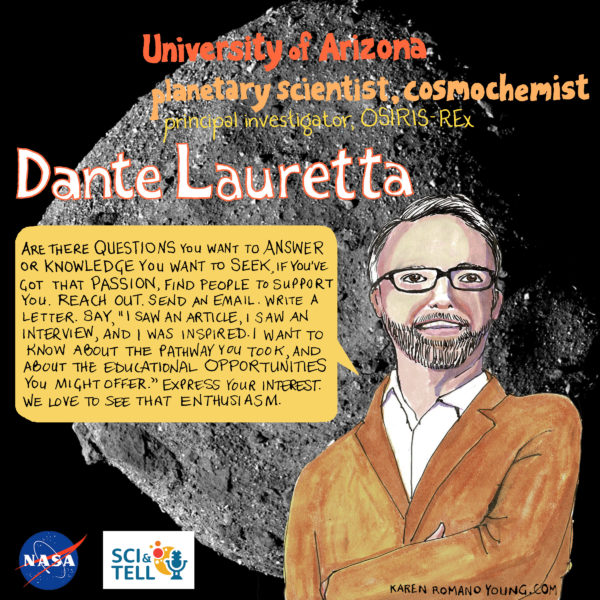

Dante Lauretta, Regents’ Professor of Planetary Science at the University of Arizona and the principal investigator for NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample mission, has been working on bringing back samples from Asteroid Bennu since 2004- and he still has two more years before he might be able to touch them.

We talked to Dante about the amount of patience required when working in science- from submitting (and getting rejected) numerous proposals to seeing births and deaths and marriages and divorces, a lot happens when working on a project for years. We also talked about how his passion for science stems from his love for exploring, and how in two years, when he finally has his asteroid samples, it will be worth a billion dollars.*

*give or take

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and Nisha Mital, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: Growing up I kind of prided myself on not going along with the crowd and being a bit of a rebel. Nothing serious, I am a scientist after all, but just enough to have a sense of “I mean, I guess that’s fine?!” Frankly, this is how I felt about space for quite some time (noting the irony that I work for an Earth & space society). I’m an ecologist so I just didn’t get why everyone loved space so much, and I was always the first to say so. But then the total solar eclipse of 2017 happened. Entire swaths of the U.S. (among other places) looked up together, to share in the awe and wonder if this moment. I wasn’t even in the direct path, but it really affected me. Since then, I’ve tried to, frankly, lose some of my attitude about space (and realistically other things. No one likes that guy.). So while I’m still partial what we have here on planet Earth, I think space is pretty darn cool.

Shane M Hanlon: Everyone has a story, even, or maybe especially, scientists. Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it. From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: Alright, let’s get into it. I’m gonna bring in Nisha introduce Dante and this episode.

Nisha Mital: On this episode, we interviewed Dante Lauretta. He’s a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona, and also the principal investigator for NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission. Dante’s been working on this project since 2004, so he talked to us about the patience required for working in STEM- and how it can be really rewarding in the end.

Shane M Hanlon: Thanks Nisha. Our interviewer was Paul Molin.

Dante Lauretta: My name is Dante Lauretta. I work at the University of Arizona. I am a Regents' Professor of Planetary Science, and I have the honor of serving as the principal investigator for NASAs OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission.

Dante Lauretta: So I'm a professor here and I teach, [00:00:30] so I teach classes in astrobiology, I teach classes in Cosmochemistry, basically looking at how the solar system formed, is there life elsewhere in the universe? And I do a lot of scientific research to address those questions as well. Traditionally, I had focused on meteorites, which are chunks of rock that fall to the earth from outer space and they come from asteroids. So we can learn a lot about the geology of the solar system by studying those samples. But they're contaminated, they come through the atmosphere, [00:01:00] there's a selection effect because only the strongest materials can survive that very violent event. And then a lot of the questions I'm interested in are related to the origin of life and there's life all over the surface of the earth. So as soon as the rock lands here, pretty much gets colonized by microbes from earth.

Paul Molin: It's so hard to tell what is from where and whatnot?

Dante Lauretta: Yeah. The contamination obscures the signal from outer space. And so we decided to solve that problem by building [00:01:30] a spacecraft and going to an asteroid and getting our own samples and spending a lot of effort to keep them clean.

Paul Molin: And what is the status on that project? Is it active? Is it finding, has it returned?

Dante Lauretta: It is on its way back home with the samples safely tucked away inside a return capsule. So we arrived at Asteroid Bennu, in 2018 and we spent over a year mapping it to select the site, to collect the sample from, we successfully [00:02:00] collected the sample in October of 2020 and we'd left the asteroid in May of 2021.

Paul Molin: And what's your estimated return?

Dante Lauretta: The samples will return to earth on September 24th 2023.

Paul Molin: A lot of these interviews we've done with a lot of people on projects like yours, and we always joke about the patience it takes to be a scientist or be involved with NASA. I don't know what jobs I'm doing in September at this point, so knowing that [crosstalk 00:02:52].

Dante Lauretta: Yeah, I've been working on this program since 2004.

Paul Molin: So exciting. And then it'll just [00:03:00] be re beginning when you get all the data to analyze?

Dante Lauretta: That's right. The whole point of the mission was to bring the sample home and then there's a lot of science that we're going to do with that sample once it's in our laboratories. Not that we didn't do amazing science at the asteroid, we had some great cameras and spectrometers and we mapped the asteroid in exquisite detail and we've published many papers about that, but I'm in the business to get that sample. I'm a chemist basically by training and so I'm really looking forward to that final phase of the science campaign.

Paul Molin: [00:03:30] And as far as volume, how much material are you able to bring back?

Dante Lauretta: We estimate about a Coke can size, full of sample from the surface of the asteroid.

Paul Molin: Cool. So it'll be a high value commodity.

Dante Lauretta: Yeah. It's a billion dollar cup of asteroid dirt.

Dante Lauretta: I was really inspired in college when I applied and was accepted to a program called the NASA Space Grant program, which is to provide undergraduate research experiences. And I didn't know what I wanted to do when I was in college, I was studying math, studying physics, studying Japanese and East Asian studies. I was trying to figure out what kind of path I wanted to go down. [00:04:30] And I saw in the school newspaper, this would have been 1992, a giant full page ad that said, "Work for NASA," and I was like, wow, man, if I could do that, then I would really be doing something I think I would love. So I applied for it and I got accepted to the program and I was assigned to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

And when I saw that, I was like, I didn't even know that was a job. There's actually people who get [00:05:00] paid to sit around and think about contacting aliens and how would we find them and how do we communicate with them, it turns out that wasn't very popular with the US Congress and that program got canceled very quickly after that in 1993. But the inspiration stuck with me, I really wanted to understand, are we alone in the universe? Are there other planets that have life on them and did that life evolve and did that life evolve like it did here on earth to the point where it could develop technology, and [00:05:30] could we find it if we did a dedicated, astronomical search for that kind of phenomena? So those big questions are what have driven me since that day.

Paul Molin: Do you remember having a, I guess that question about life outside of our world before that, or was that a triggering moment?

Dante Lauretta: I was definitely thinking about things like that, I always considered myself an explorer. I was a backpacker, [00:06:00] I did a lot of back country camping and with some buddies and we would definitely stare up at the night sky when you're out in those remote areas of wilderness and you get a clear sky view, just the beauty of the stars and to see the Milky Way galaxy and understand the motion of the planets. We were enthralled. So, we were like, wow, how cool would it be to be exploring places like that?

Paul Molin: So after that first stint at NASA [00:06:30] for that program, what was your career path from there?

Dante Lauretta: Well, I got advice very early on that studying the search for extraterrestrial intelligence was a career ending move, so I decided to focus on the formation of planets. I was like, well, if you want to understand if there's life first, you got to understand, do they have a planet to live on? And that was a legitimate area of investigation. So I went to graduate school at Washington University in St. Louis and I started [00:07:00] working on understanding the chemistry of the protoplanetary disc, which is the giant disc of gas and dust that was swirling around our young sun inside, which all the planets form. So I wanted to understand what were the elements necessary for life and how did they get incorporated into planets? And what was the likelihood of various planets across the solar system of having those key elements? And we're talking about carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, [00:07:30] phosphorous, sulfur, and sulfur was the one that I focused on for my PhD thesis. And I did a lot of work experimentally proving how you incorporate sulfur into planets and what role that could play in planetary evolution.

Paul Molin: What keeps you going on that? So finding life outside our world, looking for that [00:08:00] full-time or part-time since 1992, what keeps that drive alive, that motivation alive?

Dante Lauretta: Well, it's an awesome question. So it's amazing that I could actually develop a career to go seek answers to that kind of question. And it's been a lot of fun to get involved in a NASA spacecraft mission, to be the leader of a program like this, even though it's been a long time, the job has changed over that time period. I'm not always doing the same kind of thing. [00:08:30] In the early days, you're talking to engineers, you're trying to explain the science and the measurements that you want to make in a way that they can go and build the devices that you need. So you do a lot of system engineering. You're looking at PowerPoint diagrams of what the spacecraft is going to look like. And then you get all that settled and agreed on, and then you go into the build. And that was a really fun time period.

It was built by Lockheed Martin in Littleton, Colorado. I got to go to the high [00:09:00] bay, which is what they call the clean room, where they assemble these spacecraft on a regular basis and watch this amazing vehicle come together. It's a lot like a high performance race car, it's just got to behave, it's got to perform absolutely perfectly. You're putting it through a very demanding environment, and it felt like that. I used to do a lot of work on cars when I was a kid, a teenager and so I felt like being back in the shop, seeing this amazing thing come together and at the end, [00:09:30] you fire up that engine and you just get that feeling like, yes, we built this, we put this thing back together and you can just feel that roar. Well, that was amplified a million times when that rocket took off from Cape Canaveral in 2016 with the spacecraft on board. But it was that same feeling like we built this and now it's off to go do this job, it's on this amazing journey into deep space.

Paul Molin: I can't even imagine how exciting it's going to be as you get closer and closer to that return with those samples.

Dante Lauretta: [00:10:00] Yeah. It's two years out right now, so I don't try to get too excited about it because I know, as you mentioned, patience is a virtue in this business, so you got to be patient. But we're having a lot of fun planning on what we're going to do once those samples are back on earth and I'm talking to laboratories all around the world that have specialized capabilities that we're lining up, how we're going to get them some sample and the kind of measurements that they're going to make. And how we're going to roll all that up into understanding the formation [00:10:30] of the solar system.

Paul Molin: When you look back at your career to this point, are there any failures, I guess, times that things didn't go quite as planned. And when those things happen, how do you move on or readjust or refocus to just not get so beat down by them?

Dante Lauretta: Absolutely. The NASA process for getting your mission funded is pretty arduous. So [00:11:00] I mentioned, I started on the program in 2004 and that was the first proposal, that was rejected and that was a blow, but we knew we were new, we were just getting started. So we were like, okay, this is good, we got some feedback, let's rewrite this. So you've got to commit, it's another year to write another proposal. We wrote that one, that one made it into what NASA calls phase A, and I like to compare this process to the NCAA Basketball Tournament. So NASA puts out a call [00:11:30] for proposals and says, we're going to pick a new mission to go somewhere in the solar system and this is your opportunity to communicate to the agency, what you think the research priorities should be.

And then, so a couple dozen teams will enter that tournament, will tell NASA we're interested, here's our idea. And then you make it to the championship game, which is what NASA calls phase A. You gets selected out of that big pool and then you're in the finals, but there's a couple other teams too and NASA [00:12:00] is only going to pick one of them, so you've got another year of detailed study. We made it to that championship game, and then we lost. And at that point it was now 2007, I'd been writing this proposal for three years and you're done, it's like NASA said, "Thanks, but no, thanks. We're going to go fly to the moon, we're not interested in your asteroid this round." So that was probably one of the toughest moments because you're like, okay, we made it to the championship game and we lost. There's nothing quite like that feeling, but [00:12:30] it was really strong. We felt like we almost got there, there was just a few things that we needed to fix and this would have won.

So that was what kept us going, that and the fact that the team was really great when we were working together, you just had this comradery, we were all united, we were unified in our vision of what we needed to do, we were on a mission, and we had the common purpose. And that's a really special thing, when you get involved in a team and everything is clicking and everybody's [00:13:00] complimenting each other, thinking through problems together, it's a really fun environment. So I was like, okay, I'll do this one more time. I said, "I'll go back for a third shot and then this is it, if NASA declines again, then I'm going to go think of something else I want to do, because I don't want to spend a decade and have no effort to show for it."

So we went into the NASA New Frontiers program, which was a different program than we had competed in before, we were competing in Discovery. And New Frontiers had a bigger budget, which helped us solve [00:13:30] a lot of the technical problems that we had on the spacecraft. And so we submitted that proposal in 2009, so now I'd been working five years on the mission. We made phase A, again, we made it back to the championship game in 2010 and then in 2011, we won and NASA selected the mission and we were able to go, so it was seven years of proposal writing to get to that stage. And there was a lot of setbacks. And then unfortunately the biggest [00:14:00] setback occurred just four short months after we were selected, my mentor and the leader of the program at the time Dr. Mike Drake passed away.

And that was a huge emotional blow to me and to the team because I was young back then and he hired me here onto the faculty at the University of Arizona. And he brought me on to that project and to lose him and to know that all of a sudden now I was going to have to step up and lead this program was [00:14:30] really difficult time. Just the doubt of, could I do it? Was I ready? Everybody was asking that, not just me, so I had to convince myself and then convince everybody else that yeah, I could step up and take the reins of this program and lead it successfully. And then just losing your friend that you'd worked side by side for seven years with, your mentor your father figure, that was devastating. So it took me a long time to get over that.

Paul Molin: It's one thing when we talk [00:15:00] about the duration of these projects, there probably are, it's probably not uncommon for personnel who are intimately involved at the beginning of projects, not to, whether they retire or pass on or whatever it is, or move to different projects, to not be involved, to see the fruits of that work. That's got to be a difficult thing for the people who end up having to watch from a distance and also the people who were involved in the project all the way through.

Dante Lauretta: Yeah, I can say now, let me think, 2004 to 2021, 17 [00:15:30] years, I've been working on the program, I've seen everything, I've seen births and I've seen deaths and I've seen marriages and I've seen divorces. People have come onto the team and that's really exciting when you hire somebody, people have left the team and in goodwill, but it's just been an enormous change. And it's a big team so you see a lot of things like that. And you just, at first, it's hard, but then you just learn that's how life goes and when you're working on a program for 20 years, you're going to see a lot of things.

Paul Molin: What advice do you give to young folks who are looking at the sciences as [00:32:30] where to go, the next step of their education, or even as a career?

Dante Lauretta: …for me, science is curiosity driven, so if you are curious, if you've got that passion, there's questions you want to answer or knowledge you want to seek, then you got to channel that and follow that and find people who will support you. I guarantee you, when students come to me and they express that interest, I do everything I can to help them. And so we love to see that enthusiasm. So reach out, [00:33:00] send us an email, write us a letter saying, "I saw a news article, I saw an interview and I was really inspired and I'd love to learn more. And I want to know about your educational opportunities or the pathway that you took to get there." So there is lots of ways to get involved in science, and I can tell you, we are desperately short on people who are trained in science and engineering and technology.

And so there's a lot of opportunities and there's a lot of initiatives to recruit people into these fields. So there's scholarships, [00:33:30] there's fellowships, there's all support networks that are out there, mentoring programs. So follow your passion and we will help you.

Paul Molin: Do you think when you get those samples back in a couple of years, do you have a presumption of what you're going to find or is there potential for just, mind blowing, didn't see this coming type [00:21:00] of discovery?

Dante Lauretta: I would say both. So we had spectrometers that surveyed the asteroid in the visible and infrared wavelengths, and those provide a fair bit of information about the composition of the surface. So we think we have a very wet asteroid in the sense that the dominant mineralogy seems to be clays and clay minerals have water inside their structure. And so that's really exciting [00:21:30] for us because one of the things we want to know is how did earth get its water and why is earth a habitable planet? And we think these asteroids delivered that. So we're expecting a lot of clay minerals. We have seen carbon on the surface in the spectral data, both in the form of organic molecules, which means that they're bound with hydrogen and in minerals called carbonates. So we expect that we have accurately characterized the surface of the asteroid.

That said, Benuu, which is the target asteroid [00:22:00] that we got the sample from is a trickster. And it has done nothing but literally throw curve balls at us since we started studying it. So I expect that those surprises are going to continue. Bennu, has got one last shock for us when we get that sample, there's going to be something in there we weren't expecting, and what makes science really fun.

Paul Molin: In 1992, when you first started getting exposed [00:22:30] to NASA, I believe it was the date you said, would we ever dreamed of landing a spacecraft on an asteroid? How fast is that technology evolving?

Dante Lauretta: Well, there were people thinking about asteroid sample return in the 1990s, so the concept wasn't new with us, there was other teams that should have worked through the design. And it was achievable back then, it would have been a lot more challenging, but the technology, we actually, the spacecraft, the technology on the spacecraft is [00:23:00] not cutting edge, it's very tried and true. Like the propulsion system is a mono propellant propulsion system, which has been used for 50 years. And so we were using very reliable hardware for the mission. The technology came in the software where we had to end up executing a pinpoint landing on the surface because the surface was so rugged and rocky, that was one of the big surprises, we didn't expect that based on the telescope data that we had been studying.

And so we had [00:23:30] to make the spacecraft smart and we had to put in some decision-making capability and an autonomous guidance system. So it could take pictures of the surface and it could figure out where it was relative where it needed to be, and then make corrections to a trajectory to get there. And I don't know if that would have been possible in the 1990s. I think that this kind of autonomous guidance technology has come a long way since then.

Dante Lauretta: To me it shows you what people can do when they cooperate and they work together and they unify on a common vision [00:24:30] and a common goal. I mean, OSIRIS-REx required over a thousand people all over the world, working dedicated to the mission success. And these are things that require huge teams and it requires that you act as a team, that you focus together on a mission. So I like that to be one of our key messages that we get out there. Humans are capable of amazing things as long as we work together.

Shane M Hanlon: Teamwork makes the dream work, and I want to thank Dante for talking to my amazing team, without whom Sci & Tell wouldn’t be possible. Special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible, to Nisha for producing, and to Paul Molin for conducting the interview.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From these scientists in our respective home studios, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.