Melissa Scruggs: From GED to Volcano Ph.D.

01 April 2021

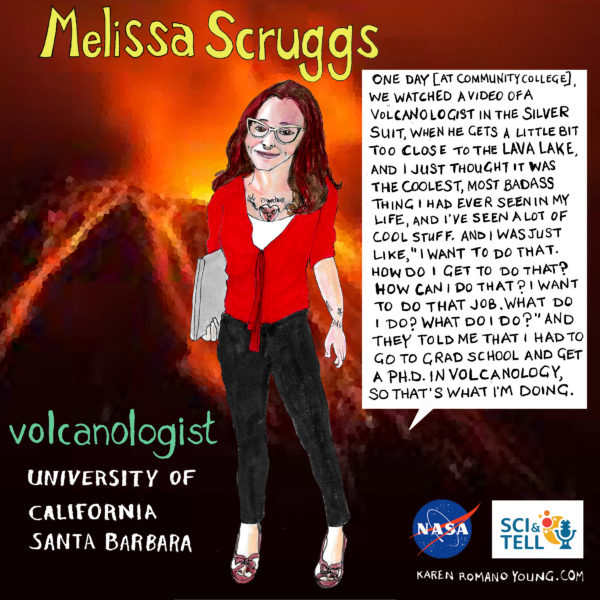

Melissa Scruggs’s path to becoming a scientist is anything but straightforward. From getting pregnant in, and dropping out of high school, to being a single mom taking classes at a community college, to learning later in life that she has autism, Melissa has overcome a lot. But oh man is she kicking ass now as a Ph.D. candidate studying volcanology in beautiful California. We talked with Melissa about adversity, perseverance, and her dream to someday wear a certain silver suit.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: Back when we traveled places, I’d go to Alaska every year to host a workshop…in the middle of January. Where most my friends cringed at this idea, I relished it. I’m a skier and so I’d take a few days after my work duties were done to head to a resort right outside of Anchorage and get in some great skiing that I couldn’t experience on the east coast. It’s on one of these trips that one evening, or I guess early morning, I’m in my bed at the resort and I feel a slight shaking. It actually takes me a few seconds to wake up because it was kind of pleasant. In my post-sleep haze, I can’t really figure out what’s going on. I initially think that someone what having one heck of a party that it was shaking my room. Or maybe it was really windy out. About five seconds into this it hits me – Oh, crap, this is an earthquake. I’d never experienced an earthquake before and by time I realized I should probably take some action, it was over. I’m embarrassed to say that I did AGU bad by lack of reaction. But it was mild and there weren’t any aftershocks, so I figured I’d just go back to bed. Then my phone blew phone…with tsunami warnings. Turns out the resort I was staying at is basically as sea level. I monitored the situation on my phone, checked with other hotel guests, and it turned out that no tsunami ever formed. Crisis averted!

The next morning at the local coffee shop I overheard some locals talking about how the moment the earthquake hit, they all piled into their cars and headed for higher ground. And I kept, not-inconspicuously, quiet. Well, now I know – even though I hope that’s knowledge that I never have to use.

Shane M Hanlon: Everyone has a story, even, or maybe especially, scientists.

Science affects each and every one of us. Let's talk about it.

From the American Geophysical Union, I'm Shane Hanlon, and this is Sci & Tell.

Shane M Hanlon: Alright, today we wanted to switch it up a little bit. We’re going to stick with Earth and space science but really focus on that first part. We chatted with Melissa Scruggs, Ph.D. candidate at the University of California Santa Barbara, where she models volcano behavior. Basically, she’s a volcanologist. And while volcanic activity can lead to seismic activity, i.e., earthquakes, we got much deeper (get it?!) with Melissa.

Our interviewer was Paul Molin.

Melissa Scruggs:

Hi, my name is Melissa Scruggs. I am a grad student and PhD candidate at the University of California in Santa Barbara. I study what makes volcanoes erupt.

Melissa Scruggs:

You would be amazed at the number of people who live in the immediate vicinity of an active volcano and don't recognize the risk that they're at. So for example, I think Vesuvius, I want to say Vesuvius ... Vesuvius is still active. Everybody knows about its 79 AD eruption, but most people don't realize that it had a major eruption in 1944. And you can actually find that archive footage on YouTube. It's very cool.

Melissa Scruggs:

And there are something like, what, 3 million people who live within the vicinity of Vesuvius? And to them, it's a volcano, but something's just not clicking there in their heads. They don't realize, "Okay, this is an active volcano, though. I need to learn about it and what could happen, and be prepared for something, at least realize what I live on or around." So I think that because of the risk that they can pose, I think that

Paul Molin:

And does your research help with any predicting when things will erupt or warning signs as well, for those people who decide to live near a volcano?

Melissa Scruggs:

I'm actually really glad that you asked your question that way, because you cannot predict an eruption. You can forecast an eruption, and here's the difference. A prediction implies a time, a place, and a magnitude. So you could say, "This volcano will erupt on February 31st, 2022, at 9:37 AM." That's a prediction. A forecast is more what we can do. We can say, "Okay, well, there's some activity here. There are some earthquakes," because magma as it moves through the ground can give off a certain type of earthquake signature that can allow volcano scientists to ... I don't want to say predict, but to have a better idea of where the magma might be traveling towards and how fast and how much, potentially. There's a whole lot of ifs, and that's only if it's a really, really well-studied volcano. Most volcanoes are not well-monitored.

Paul Molin:

What got you into science?

Melissa Scruggs:

I didn't really have an aha moment at all. I do remember having a high school teacher ... I loved my high school chemistry teacher. Her name was Dr. [Sabatka]. She was super cool. I remember making esters in her class, and that was super fun. And I just really liked chemistry with her a lot.

Paul Molin:

So, when you decided to then go to college or university, what do you think pushed you towards volcanoes?

Melissa Scruggs:

I didn't take a normal path to university. I actually didn't finish high school, even. So, I got pregnant in high school. And I dropped out halfway through my senior year because I needed to work full-time. I got my GED and started doing community college, working full-time, single mom. Yeah, I got a job as a secretary for a lawyer, and was just like, "Yeah, okay. This isn't so bad, and you can make money. I guess I'll do this."

Melissa Scruggs:

And so, I got a paralegal certificate and transferred to the four-year university and was like, "Okay, I'll do pre-law, because this is fine. This is easy." I know that not all law is easy, but for the stuff that I was doing, it wasn't that bad. And I was like, "I'll be a lawyer. I can make money. I'm good at this. It's not that hard. It's not that terrible. I could do this." But the university I went to, which was in Kansas City, which is where I'm from, they had a pre-law track, but there was no pre-law major, so I still had to pick a major.

Melissa Scruggs:

And I have no idea why, but I decided to be an environmental lawyer. I think it was because all the lawyers I worked for, I did family law, bankruptcy, personal injury and work comp, and it was just nothing but pain. I hated it, so I wanted to do some good. So yeah, so I was actually supposed to do environmental law. I was an environmental science major. I took an environmental science class, and I did not enjoy it that much. I didn't hate it. I liked it, I just didn't enjoy it. It just didn't get to me.

[O]ne of the next classes that I took was mineralogy, and that is a geology class where you learn all about minerals. And that's where they get you, with the shiny crystals, and I was hooked, absolutely hooked. I loved it.

Melissa Scruggs:

When I was in undergrad, I took this class called The Archeology of Ancient Disasters. And it was really fun. It was eye-opening. I loved it.

Melissa Scruggs:

And one day, we watched a video of a volcanologist in the silver suit, when he gets a little bit too close to the lava lake, and I just thought it was the coolest, most badass thing I had ever seen in my life, and I've seen a lot of cool stuff. And I was just like, "I want to do that. How do I get to do that? How can I do that? I want to do that job. What do I do? What do I do?" And they told me that I had to go to grad school and get a PhD in volcanology, so that's what I'm doing.

Paul Molin:

What do you think... have been the biggest hurdles to getting to where you are so far?

Melissa Scruggs:

Obviously, I had a kid in high school. And that in and of itself makes things more difficult. But I don't really consider my kid a hurdle because I've just always had her with me, and I don't really know anything other than that. So it's not so much like a new thing that has to be jumped over, because it's always been just us. I've always just been doing school and work and kid. For me, I think the biggest hurdle is communication skills, surprisingly. I'd say definitely coming from a first-generation grad student, because I'm the first in my family to go to grad school, being a teen mom, and having some communication difficulties. A few months ago, I found out that I'm autistic. And now a lot of things are starting to make sense.

Melissa Scruggs:

One of the reasons why I applied to be in the Voices for Science program, which is a science communication program with American Geophysical Union ... But one of the reasons why I first applied for that program was because I felt like whatever I was saying never really came across quite right, and I wasn't able to effectively communicate what I needed to. And whenever I say things, I feel like they always just come out wrong, and people misinterpret what I say or it can turn somebody off. I've definitely lost out jobs and things like that, lots of friends, and now I understand why, so I'm more at peace with it. Before, I didn't really get it, now I understand why, so I'm more okay with it.

Melissa Scruggs:

So now I'm starting to take classes to work on communicating, because I didn't realize that I think in pictures in my head. So I spend half the time trying to understand what somebody is saying to me, and the other half trying to watch the movie that's playing in my head, which is what they're trying to say.

Melissa Scruggs:

And so when I'm trying to talk to you, if I'm trying to recall an event or describe something, I have to try to figure out what's going on in the picture. It's like trying to explain a movie to somebody who's never seen it. It's hard. And so I'm having to learn to talk in a whole new language. And to me, I think that's really been a bigger hurdle; just how I have relationships with people has been a bigger hurdle to me than my daughter.

I've been in school her whole life, literally. She's going to graduate high school the same year I get my PhD, hopefully. Knock on wood. But I'm incredibly proud that I've been able to get to this point. I did not have a really great support structure growing up, and even just going through college and grad school and dealing with being a parent is hard. And it's really, really difficult. So I'm really proud of where I am, but I don't know that I would say that this is my personal achievement, because I haven't achieved it yet. I'm still trying. But I'm still proud of where I've gotten to.

Melissa Scruggs:

Sometimes when you have the really bad days and you have a project ethically fail and you have to come up with a whole third of your PhD on the fly, sometimes those days can be hard.

I went down this horrible rabbit hole of numbers and just statistics, and it made my brain topsy-turvy. Essentially, it came down to I was trying to figure out how linear a line had to be, to be considered a line. So yeah, think about that for a second. And it was like falling down the worst Wikipedia rabbit hole ever, for like a year and a half. And I had convinced myself that I was so right. I still am convinced, though.

Melissa Scruggs:

But what I hadn't noticed is I had made a very small mathematical error. And my advisor saw it and then it made the problem I was trying to solve not as important ... I don't want to say not as important, but it wasn't as much of an issue. It's still an issue, but it's not as much as I thought it was, if that makes sense. And so, he got pretty upset with me. He felt like I had misled him. He really felt hurt, like I had misled him. And I didn't realize. I truly thought that I was right.

Melissa Scruggs:

I had already gone through my qualifying exams, even. So I had qualified to be a PhD candidate, and I was supposed to have maybe a year and a half left. And about three months after I passed my quals, he decided that I couldn't use this project anymore, and I was going to have to come up with a whole new project to do a third of my PhD on. And so, that was really bad. I considered dropping out. I'm really glad I didn't, because I got a cool project, and now I work on Kīlauea Volcano. That's way cooler than thinking about lines theoretically.

Melissa Scruggs:

I don't have work/life balance. I wish that I did. I managed it by not having a social life. I have a few very good, close friends, but I mostly managed it by giving up my social life. And it also helped because when I was going through the hardest parts of being a mom, like when your kids are little, little, and in undergrad and trying to figure all this stuff out, I was like 17 to 21, 22, so that's when you can pull all the all-nighters.

Melissa Scruggs:

I could stay up four days in a row and rock a midterm, and have a toddler, because I had all the energy. I could not do that now. I could not do that now. I can barely hold it together right now. I'm old. But yeah, I think what made all the difference was how young I was. It helped so much with the energy. And now, I'm not so great at the work/life balance. A PhD is much harder than a master's and undergrad. So I've been taking longer than I would have liked to, just because of life. Life happens.

I don't know what's next. So, I'm actually married now. But my husband and I have never lived together, because I go to school, and he works. And so, I went off to grad school, and we've been in a long-distance marriage. So honestly, I'm just really excited to finally just be able to actually be a couple and live together, and hopefully we can ... It's going to be a lot harder for me to find a job, I think, than him. So we're going to work together. And we're at a point where everything is just so up in the air, that we can finally make these life decisions as a couple. So I'm excited for that, truthfully.

Shane M Hanlon:

I’ve been in multiple long-distance relationships and I didn’t love it. I’m fortunate now that my partner and I are under one roof and I’m excited for Melissa to be able to experience that as well.

Special thanks to NASA for making this episode possible, to Paul Molin for conducting the interview, and to Collin Warren for audio production.

If you like what you've heard, stay tuned for future episodes. You can subscribe to Sci & Tell wherever you get your podcasts and find us a sciandtell, all spelled out, .org.

From this scientist in the studio, to all of you out there in the world, thanks for listening to our stories.